Wednesday, November 15, 2006

What if George Bailey had vertigo?

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post is part of the Hitchcock Blog-a-Thon being coordinated at The Film Vituperatem.

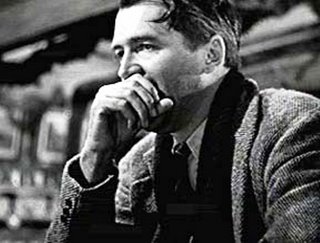

By Edward Copeland

As a blizzard bears down on him, a despondent George Bailey stares off a bridge into a storm-tossed river, contemplating what it would be like if he'd never been born. Before he can take his final plunge though, another man slices through the air and into the water, prompting George to save the stranger's life, much as Scottie Ferguson would save Madeleine from the San Francisco drink 12 years later in a different film by a different director. George and Scottie were brought to screen life by the same actor, James Stewart, but the films in which these two characters debuted came courtesy of two very different directors — Frank Capra and Alfred Hitchcock.

Capra used Stewart first and, when examined, the director's development of an all-American image for Stewart as the embodiment of the everyman Hitchcock needed to fully explore the average person's darker side. If it weren't for Capra's work in three films, most specifically Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and It's a Wonderful Life, Hitchcock would have had more work to do when he used Stewart in four films. As it turned out, Capra's part in generating Stewart's image lent Stewart added dimensions that Hitchcock ran with from the very first time he aimed his camera on him. Donald Spoto wrote in The Art of Alfred Hitchcock:

Stewart's professional persona is strikingly inverted in the Hitchcock films, and that is a perfect paradigm for the surprise his audience should feel in locating a similar darkness within themselves. We do not generally see James Stewart in these terms. But of course in Hitchcock's film, what you see isn't what you get.

It was Stewart's second film for Capra, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in 1939, that Stewart firmly established himself as the ultimate Capra hero. Jefferson Smith was a slightly dull but completely kind-hearted man who finds himself the pawn of powerful politicians' power games. He suddenly finds himself a senator, basking in the glow of serving the public good in the world's symbolic center of democratic principles, principles that he soon learns are slightly perverted. As this good man attempts to stand his moral ground, his loss of innocence and growing cynicism turns into a battle-cry filibuster for freedom. One popular misconception about Capra's works, commonly referred to as "Capracorn," is that everything in is goodness and light in the Capra universe, when nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the presence of corruption and dark elements in Capra's films with Stewart and in general could be seen as sowing the seeds in Hitchcock's head to explore his own areas of interest through an appealing and sympathetic actor such as Stewart.

It can be no accident that the time lapse between the ultimate fruition of the Capra-Stewart relationship (It's a Wonderful Life) and Stewart's first work with Hitchcock (Rope) was only two years. In fact, the way Hitchcock inverted and expanded on Stewart's Capra-created screen image may be best exemplified when comparing those two specific films. A minor technical difference between Capra and Hitchcock's use of Stewart could be read as symbolic. All of Stewart's work with Capra was in black-and-white, in a universe where good men can have bad times but where they always triumph in the end, a world where heroes and villains are clearly delineated. When Stewart prepared to work for Hitchcock, the Master of Suspense chose this film as the time for his first venture into color filmmaking, a move that could be said to "color" the characters Stewart played for Capra and paint more layers onto them.

The subtexts of these two films are quite interesting. Consider that George Bailey believes that life would have been better if he'd never been born. Rope's Rupert Cadell wouldn't go that far, but theoretically he holds the view that murder should be a privilege reserved for the superior. Both Cadell and Bailey have their beliefs proven wrong: Bailey through a journey through a world that never knew him, Cadell by having his theories fulfilled and thrown back in his face. Both journeys, one fantasy and one real, horrify in their own ways but both end with the same result — both characters end up with a renewed sense of life. However, whereas George Bailey's is one of optimism and restored faith in himself and mankind, Cadell's is one of questioning one's own philosophy. George Bailey realizes powerfully that every life touches others in important ways. Rupert Cadell finds that book-learned approaches to meaningless lives can have results deadly to all of mankind if put into action.

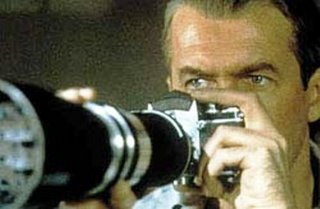

Another interesting overlap between Cadell and another Capra-Stewart creation, Jefferson Smith, are similar professions or former professions of the two characters. Smith was a scoutmaster, leading a group of faithful boys who helped carry out his noble civic duties. The implication clearly is that these kids will grow up to serve society well. In Rope, Cadell was a former housemaster to the characters of Brandon and Philip and the theories and philosophies he passed on to them ended up creating two men who test Cadell's beliefs out by murdering one of their fellow pupils. Another similarity between George Bailey and three Hitchcock characters Stewart created (in Rope, Rear Window and Vertigo) is that all four characters sustained injuries in some sort of arguably heroic duty. The young George Bailey suffered a hearing loss following his ice rescue of his younger brother. Rupert Cadell's handicap has become a limp, one attributed to service during wartime. The limp became a broken leg for the overzealous photographer Jeffries in Rear Window before Vertigo transformed an injury that required a corset or cane into a purely psychological wound for Scottie Ferguson.

It seems perfectly appropriate that Stewart's progression through his Hitchcock films should eventually become completely psychological, since Hitchcock's method of working focused on implications from the actors, not actualizations. Stewart's performances, albeit among the greatest of his career, in Hitchcock's movies grew more and more subtly. In contrast, the Stewart of Capra's films wears his emotions on his sleeve. Take this piece of dialogue from It's a Wonderful Life: "Now you listen to me. I don't want any plastics and I don't want any ground floors and I don't want to get married EVER to ANYONE. Do you understand that? I want to do what I want to do!"

Comparatively, these lines could just have as easily been spoken by Rear Window's Jeff to Grace Kelly's Lisa instead of George Bailey saying them to Donna Reed's Mary. Therein lies a crucial component of Stewart's Capra persona that Hitchcock appropriates. Jeff's aversion to marriage doesn't have to be spelled out because Stewart has brought that part of his persona to the movie with him from his earlier role as George Bailey. Coincidentally or not, both George and Jeff end up involved despite themselves. Also, in an amusing side note, both Rear Window and It's a Wonderful Life contain sequences involving Stewart's characters engaging in the practice of girlwatching. Stewart's cinematic baggage was important to the Hitchcock films for more reasons than just placing a dark spin on a likable performer. Stewart was more than just someone associated with Capra, he was the epitome of and symbolic representation of the entire Capra universe which, to some extent, Hitchcock tried to expose throughout his career. One can't help but wonder if Shadow of a Doubt had been made later and Stewart agreed to play a killer, whether he could have made for an interesting Uncle Charley. Granted, Joseph Cotten was perfect in the role, but it could have carried so much more weight to see the idyllic Stewart playing a serial murderer of widows. Stewart's transformation in the Hitchcock films even shows signs of pervading past the obvious twists seen in Stewart's characters.

Early in Rope, before Rupert Cadell has entered the picture, John Dall's character of Brandon shows definite signs of Stewart-like behavior as he tries to calm his accomplice's fears. In fact, in some early scenes where he talks of Rupert, Dall's facial expressions even suggest Stewart's trademark intelligent "aw, shucks" quality quite explicitly. Hitchcock seems quite enamored of the world Capra creates, loving to show its dark underbelly. It is difficult to find a reverse process in Capra's films — except for the strange presence of a crow in practically every scene set in the Bailey Building and Loan in It's a Wonderful Life. While birds represent chaos to Hitchcock, it remains unclear what significance the black bird provides for Capra in his holiday classic, though it seems unlikely the crow flew off with the missing funds that George's uncle misplaced.

The most important aspect of what Stewart brings to a Hitchcock film could be what Spoto describes in The Dark Side of Genius as an attempt for Hitchcock to develop a successful surrogate for himself. Spoto wrote in reference to Rear Window:

James Stewart would serve as Hitchcock's chair-bound alter ego, a photographer whose mobility is limited by head-to-toe plaster cast. Stewart is clearly a Hitchcock surrogate in Rear Window. The character's wheelchair resembles a director's chair; with a long lens he spies on his neighbors (seen through the rectangular "screens" of their open windows). ... Also like Hitchcock, he watches and admires as a woman models a dress and a nightgown for him.

Also, as Spoto points out later in the same book:

Stewart was closer to a representation of Hitchcock himself than any presence until Sean Connery's in Marnie. Elsewhere one of Hollywood's clearest exponents of the ordinary man as hero, Stewart's image was reshaped by Hitchcock to conform to much in his own psyche. He is in important ways what Hitchcock considered himself: the theorist of murder (in Rope); the protective but decidedly manipulative husband and father (in The Man Who Knew Too Much); the obsessed, guilt-ridden romantic pursuer (in Vertigo).

Stewart, thanks to Capra's grooming as that ordinary, upstanding American, gave Hitchcock the perfect platform to show the ironies and dark side of the

charmed life. A patriotic man can leer at women just as well as a corrupt man can. Similarly, the oppressed masses can plot murder just as well as suicide, even though they both know that neither act is morally justified. The most important ingredient that Hitchcock added to the Capra recipe were the psychological elements. In Capra's films, Stewart never was haunted by hangups or lost loves, he just had everyday burdens. It is part of Hitchcock's genius that he could play off this image and expand on it. If Capra had explored these elements, George Bailey might have been the one suffering from vertigo and he would never have been able to save Clarence on his way to helping Clarence earn his wings. Regardless of the differences and similarities, what remains are great examples of cinema by two very different directors. The audience should be grateful to Hitchcock and Stewart for allowing the audience to synthesize both Stewarts and see both sides of the same coin. For all of its glory, black-and-white situations and people don't happen often, usually merging into areas of gray and Hitchcock explored this to great success by putting James Stewart in color.

charmed life. A patriotic man can leer at women just as well as a corrupt man can. Similarly, the oppressed masses can plot murder just as well as suicide, even though they both know that neither act is morally justified. The most important ingredient that Hitchcock added to the Capra recipe were the psychological elements. In Capra's films, Stewart never was haunted by hangups or lost loves, he just had everyday burdens. It is part of Hitchcock's genius that he could play off this image and expand on it. If Capra had explored these elements, George Bailey might have been the one suffering from vertigo and he would never have been able to save Clarence on his way to helping Clarence earn his wings. Regardless of the differences and similarities, what remains are great examples of cinema by two very different directors. The audience should be grateful to Hitchcock and Stewart for allowing the audience to synthesize both Stewarts and see both sides of the same coin. For all of its glory, black-and-white situations and people don't happen often, usually merging into areas of gray and Hitchcock explored this to great success by putting James Stewart in color.Tweet

Labels: Blog-a-thons, Capra, Connery, Hitchcock, J. Stewart, Joseph Cotten

Comments:

<< Home

Wow! What a fruitful comparison. I guess you could say that Capra packed Stewart's baggage, and Hitchcock carried it someplace unexpected. Or..um, something like that. This is your best piece yet.

I'm embarrassed to say that the only Mann/Stewart Western I've seen is Winchester 73, though Rope still predates it by two years. Also, it seems the parallels between Capra's films and Hitchcock's are slightly clearer since all were "contemporary" pieces instead of period Westerns. It also might be attributable to an interest on Stewart's part in this time period, since he ended the 1950s in Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder.

Love this connection. Admittedly I'm far more in the Hitchcock camp than the Capra one, but this post makes me want to watch It's a Wonderful Life again, for what would be the first time in well over a decade.

Have you seen The Mortal Storm from 1940? If not, you should. It's a very early Stewart role in a dark film. Probably Frank Borzage's greatest masterpiece, a romantic tragedy set against the rise of the Nazis in Europe.

Have you seen The Mortal Storm from 1940? If not, you should. It's a very early Stewart role in a dark film. Probably Frank Borzage's greatest masterpiece, a romantic tragedy set against the rise of the Nazis in Europe.

It's funny, Jimmy Stewart is probably my favorite big movie star type actor, but I never really thought to juxtapose his Capra characters with his Hitchcock characters.

You didn't allude to it, but it seems like every time someone writes about Stewart, they mention that after returning from being a decorated pilot in WWII, he let it be known that he was interested in playing darker roles than before and how that lead to his association with Anthony Mann westerns -- but it certainly seems to apply to the Hitchcock films (with the exception of "Man Who Knew Too Much", probably) and even "Wonderful Life", which goes to some very, very dark places before George sees the light.

You didn't allude to it, but it seems like every time someone writes about Stewart, they mention that after returning from being a decorated pilot in WWII, he let it be known that he was interested in playing darker roles than before and how that lead to his association with Anthony Mann westerns -- but it certainly seems to apply to the Hitchcock films (with the exception of "Man Who Knew Too Much", probably) and even "Wonderful Life", which goes to some very, very dark places before George sees the light.

An excellent assessment of Stewart's work for both directors. I actually think It's a Wonderful Life may represent the "darkest" work of Stewart's career - which may seem odd given how many people judge the film in terms of its sentimentality and life-affirming message. But the later portion of the film allows the actor to express a kind of fatalism and anger that no other director - not even Hitchcock - ever managed to elicit from Stewart either before or after. The film dared to show the sense of anger and impotence experienced by every clean-cut, All-American boy who has come to feel like a prisoner of his own life - George Bailey has spent his entire life scarficing his own dreams to accomodate the needs of others - and Stewart is brave enough to show the extent to which a life of compromise has taken its toll. The scene in George Bailey takes out his years of anger and frustration on his family (whom, on some level, he blames for the fact that he remained "stuck" in Bedford Falls with a job he hates), reducing his children to tears, is among the most startling the actor ever attempted.

Post a Comment

<< Home