Monday, January 18, 2010

In Texas, you're on your own

By Edward Copeland

I remember seeing Blood Simple for the first time so clearly. I was a sophomore in high school and Siskel & Ebert had bellowed its praises on their show and now it had shown up on the "Bijou" screen of our local AMC theater. I went with my parents and my mind exploded. It was as if I were witnessing the birth, no scratch that, the major announcement of new filmmaking talent that you don't usually see in a debut. This must have been similar to what film aficionados felt the first time they saw Orson Welles' Citizen Kane or Francois Truffaut's The 400 Blows. Who starts a film career this assured? It was astounding and 25 years later after the Coen Brothers arrived on the national scene, Blood Simple still astounds.

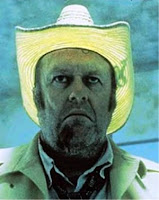

I had seen the character actor M. Emmet Walsh before and I've seen him since, but he's never had a better role or given a better performance than that of the private detective in Blood Simple. (Some sources give his character name as Loren Visser, which is what he was named in the screenplay, but in the film's credits, he's listed simply as private detective.) It's Walsh's voice we hear first in this pseudo-noir as he explains that the world is full of complainers and go ahead and ask your friends for help and watch them fly, a lesson I've painfully learned from experience over the past couple of years. He extols the idea of the way it is supposed to work in Soviet Russia, with each person pulling for the other guy. However, as the private detective explains (not that we know who he is or what he does yet), we're in Texas and there you are on your own, because nothing comes with a guarantee. Walsh's cackle can produce laughter or shivers, depending on the situation. You're never certain if his character is a mastermind or a buffoon, but Walsh plays him brilliantly. In an ideal world, the Academy would have noticed. He certainly deserved an Oscar nomination at least, especially considering the prize went to Don Ameche, who wasn't even the best supporting actor in Cocoon, because Ameche's stand-in could breakdance.

Blood Simple actually began appearing on the American movie radar in 1984 when it started showing up on the film festival circuit, but it didn't get an actual distribution and release until this day in 1985, hence why I'm

marking today as its 25th anniversary. About a decade ago, a new DVD of Blood Simple came out which I'd never seen until last week, many years since I'd last seen the film. It comes with an introduction by Mortimer Young (really actor George Ives) and the pretense that technology had caught up with it and something called Forever Young Films has restored the film, not only digitally improving the film, but adding some things and "cutting the boring parts." Granted, it had been a long time since I'd last seen Blood Simple but nothing seemed new to me besides that introduction and everything I remember being there before, still was. More importantly, Blood Simple still plays as great as always and still amazes when you remember it is the work of debut filmmakers. In the Coen canon, I'd still place it in the top four or five alongside Raising Arizona, Miller's Crossing, No Country for Old Men and their most recent, A Serious Man. In fact, though I usually frown on remakes of good films, I grant leeway with they are foreign adaptations and I have to admit I can't wait to see what the great Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou has come up with by filming his take of Blood Simple as a period film set in a noodle shop and emphasizing the comedy.

marking today as its 25th anniversary. About a decade ago, a new DVD of Blood Simple came out which I'd never seen until last week, many years since I'd last seen the film. It comes with an introduction by Mortimer Young (really actor George Ives) and the pretense that technology had caught up with it and something called Forever Young Films has restored the film, not only digitally improving the film, but adding some things and "cutting the boring parts." Granted, it had been a long time since I'd last seen Blood Simple but nothing seemed new to me besides that introduction and everything I remember being there before, still was. More importantly, Blood Simple still plays as great as always and still amazes when you remember it is the work of debut filmmakers. In the Coen canon, I'd still place it in the top four or five alongside Raising Arizona, Miller's Crossing, No Country for Old Men and their most recent, A Serious Man. In fact, though I usually frown on remakes of good films, I grant leeway with they are foreign adaptations and I have to admit I can't wait to see what the great Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou has come up with by filming his take of Blood Simple as a period film set in a noodle shop and emphasizing the comedy.Blood Simple, of course, was not set in a Chinese noodle shop. The center of its story is a popular Texas night spot owned by the angry, sleazy and apparently well-off Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya, better known as the even sleazier but much funnier Nick Tortelli on TV's Cheers). Marty hires the detective to see if his pretty young

wife Abby (Frances McDormand, who would meet future husband Joel Coen on this film) is stepping out on him. Indeed she is — with Ray (John Getz), one of his bartenders. Needless to say, Marty does not take the news well, telling Walsh that in ancient Greece, they killed the messenger who brought them bad news. The P.I. tells Marty he knows where to find him if he needs him or if he wants to chop off his head: He can always crawl around without it. When Ray returns for his final paycheck, Marty refuses to pay and warns him that if he sets foot on his property again, he'll consider it trespassing and would be justified in shooting him. Marty also makes sure to put plenty of doubts in Ray's mind about Abby's trustworthiness. Still, the betrayal eats at Marty and he returns to the detective to hire him to murder Ray and Abby. The detective expresses some reluctance that Marty isn't smart enough to pull it off, but he agrees to do it for $10,000. He tells Marty to go fishing for a few days and he'll tell him when it's done. Then things get complicated.

wife Abby (Frances McDormand, who would meet future husband Joel Coen on this film) is stepping out on him. Indeed she is — with Ray (John Getz), one of his bartenders. Needless to say, Marty does not take the news well, telling Walsh that in ancient Greece, they killed the messenger who brought them bad news. The P.I. tells Marty he knows where to find him if he needs him or if he wants to chop off his head: He can always crawl around without it. When Ray returns for his final paycheck, Marty refuses to pay and warns him that if he sets foot on his property again, he'll consider it trespassing and would be justified in shooting him. Marty also makes sure to put plenty of doubts in Ray's mind about Abby's trustworthiness. Still, the betrayal eats at Marty and he returns to the detective to hire him to murder Ray and Abby. The detective expresses some reluctance that Marty isn't smart enough to pull it off, but he agrees to do it for $10,000. He tells Marty to go fishing for a few days and he'll tell him when it's done. Then things get complicated.

What doesn't get complicated though is the plot itself. That's not to say it isn't attention getting (detractors might call it gimmicky), but the story itself is told very efficiently. It would be easy to be confused as to what

the various characters are up to but even if you have a moment of brief puzzlement, the Coens steer you back on the right track. Simple proves an appropriate word to have in the title (as does blood, because there is a lot of it). It's essentially a five-character cast (the fifth character being another bartender, Meurice, played by Samm-Art Williams, who also is a playwright whose 1980 play Home received a Tony nomination for best play). However, as far as the Coens' filmmaking style goes, they grab you early and often. After some picturesque Texas visuals to go with Walsh's opening voiceover, we go to a conversation in a car between Ray and Abby during a driving rainstorm and each pass of the windshield wipers takes one of the actor's names with it. While film watchers have been used to hyperactive cameras for a long time, a fresh smell emanated from many of the

the various characters are up to but even if you have a moment of brief puzzlement, the Coens steer you back on the right track. Simple proves an appropriate word to have in the title (as does blood, because there is a lot of it). It's essentially a five-character cast (the fifth character being another bartender, Meurice, played by Samm-Art Williams, who also is a playwright whose 1980 play Home received a Tony nomination for best play). However, as far as the Coens' filmmaking style goes, they grab you early and often. After some picturesque Texas visuals to go with Walsh's opening voiceover, we go to a conversation in a car between Ray and Abby during a driving rainstorm and each pass of the windshield wipers takes one of the actor's names with it. While film watchers have been used to hyperactive cameras for a long time, a fresh smell emanated from many of the Coens' moves. When a shot follows the length of a bar, it stops to rise over a passed-out drunk blocking its way before resuming its journey. When Meurice jumps over the bar to change a song on the jukebox, the camera follows him back at shoe level, stopping to take note as his feet do a brief dance shuffle atop the bar. When Marty gives Ray his rather intense, profane warning about Abby, his speech gets punctuated by the sound of an insect frying in an electric bug zapper. When Marty surprisingly assaults his estranged wife, the Coens combine a zoom with a high-speed tracking shot before slamming on the brakes. The wondrous climax takes place between two people in adjacent rooms, which was referenced in its own way with the money hidden in the hotel vent in No Country for Old Men.

Coens' moves. When a shot follows the length of a bar, it stops to rise over a passed-out drunk blocking its way before resuming its journey. When Meurice jumps over the bar to change a song on the jukebox, the camera follows him back at shoe level, stopping to take note as his feet do a brief dance shuffle atop the bar. When Marty gives Ray his rather intense, profane warning about Abby, his speech gets punctuated by the sound of an insect frying in an electric bug zapper. When Marty surprisingly assaults his estranged wife, the Coens combine a zoom with a high-speed tracking shot before slamming on the brakes. The wondrous climax takes place between two people in adjacent rooms, which was referenced in its own way with the money hidden in the hotel vent in No Country for Old Men.

At the start of their filmmaking career, the Coens didn't share all the credits as they do now: Joel was the director; Ethan was the producer; and they shared writing credits. Even in their debut, some familiar collaborators were on board. Composer Carter Burwell, who has scored all the brothers' films except for O

Brother, Where Art Thou. Barry Sonnenfeld did the cinematography here as well as in Raising Arizona. Of course, Roderick Jaynes debuted as a film editor, though he had the help of Don Wiegmann. What still amazes me is how these neophyte indie filmmakers were able to secure the use of The Four Tops' "It's the Same Old Song" (used repeatedly and as a hilarious endnote in the movie), Patsy Cline's "Sweet Dreams" and "The Lady in Red" by Xavier Cugat and his Orchestra, given the unmitigated greed of the music industry which demands astronomical fees and often strip permission to use the works years later if more protection isn't paid. It was a great feat, no matter how it got done. Now of course, everyone knows who the Coen Brothers are, but 25 years ago and really through Miller's Crossing, I felt as if I was part of a secret fan club. It wasn't really until Fargo, when I'd lost my infatuation with them, that everyone seemed to discover them. I'm happy that with their work starting with No Country for Old Men, the Coens and I seem to be on the same cinematic wavelength again. Still, should we become estranged again, we'll always have Blood Simple.

Brother, Where Art Thou. Barry Sonnenfeld did the cinematography here as well as in Raising Arizona. Of course, Roderick Jaynes debuted as a film editor, though he had the help of Don Wiegmann. What still amazes me is how these neophyte indie filmmakers were able to secure the use of The Four Tops' "It's the Same Old Song" (used repeatedly and as a hilarious endnote in the movie), Patsy Cline's "Sweet Dreams" and "The Lady in Red" by Xavier Cugat and his Orchestra, given the unmitigated greed of the music industry which demands astronomical fees and often strip permission to use the works years later if more protection isn't paid. It was a great feat, no matter how it got done. Now of course, everyone knows who the Coen Brothers are, but 25 years ago and really through Miller's Crossing, I felt as if I was part of a secret fan club. It wasn't really until Fargo, when I'd lost my infatuation with them, that everyone seemed to discover them. I'm happy that with their work starting with No Country for Old Men, the Coens and I seem to be on the same cinematic wavelength again. Still, should we become estranged again, we'll always have Blood Simple.Tweet

Labels: 80s, Coens, Ebert, McDormand, Movie Tributes, Truffaut, Welles, Zhang Yimou

Comments:

<< Home

Very nice essay, Ed. I seem to recall that for TV showings of Simple they weren't able to secure the rights to It's the Same Old Song and were reduced to using a Neil Diamond ditty that really threw the picture out of whack.

The only thing that nags me about the film after all these years is the fact that Joel and Ethan had to make Marty's dog do a disappearing act halfway through the movie. I'm guessing the pooch would have interfered with the progression of the plot had it been allowed to stay put.

Post a Comment

The only thing that nags me about the film after all these years is the fact that Joel and Ethan had to make Marty's dog do a disappearing act halfway through the movie. I'm guessing the pooch would have interfered with the progression of the plot had it been allowed to stay put.

<< Home