Monday, August 29, 2011

"There is a vast difference between curing an ailment and making a sick person well"

By Edward Copeland

Joseph L. Mankiewicz accomplished something in 1949 and 1950 that has never been equaled in Oscar history: He won the awards for directing and writing in two consecutive years. John Ford also had won directing Oscars in consecutive years, but no one had won for both directing and writing as Mankiewicz did for A Letter to Three Wives and the incomparable All About Eve. That would be an impressive one-two punch for any filmmaker (and between those two films he co-wrote and directed the solid 1950 suspense drama No Way Out starring Richard Widmark and Sidney Poitier in his film debut) but in 1951, Mankiewicz made another great film, one that gets better each time I see it. Adapted from the play Dr. Praetorius by Curt Goetz, Mankiewicz wrote and directed People Will Talk, which was released 60 years ago today. It didn't receive any Oscar love, but it does contain one of Cary Grant's very best performances and aches to be re-discovered by film buffs or seen for the very first time by those who haven't.

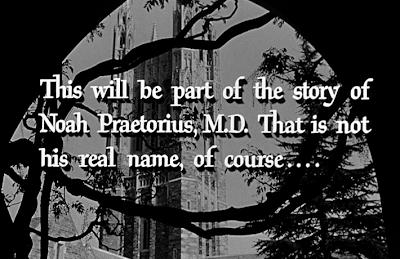

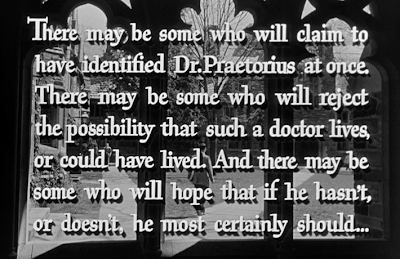

Compared to Mankiewicz's previous two films, People Will Talk defies categorization at just about every step of its story. Though those title cards shown in screenshots above indicate that this will be the story of Dr. Noah Praetorius, we won't meet him in the form of Cary Grant right away. The first person we see is none other than the Wicked Witch of the West herself, Margaret Hamilton, sitting on a bench in a hallway. A man (Hume Cronyn) comes walking down the hall when the woman addresses him as Professor Elwell. He responds, though he doesn't know who she is. It soon becomes clear that she is Sarah Pickett, a woman he's been expecting from a detective agency. Professor Rodney Elwell unlocks his office door and invites her inside. The dialogue between the pair implies that we're definitely in store for a comedy.

PICKETT: If I come in, does the door stay closed?

ELWELL: Naturally.

PICKETT: Then I don't come in.

ELWELL: Why not?

PICKETT: You know why not. You're grown up.

ELWELL: My dear Mrs. Pickett —

PICKETT: Miss Pickett — and don't butter me up.

ELWELL: I have conducted my affairs behind closed doors for 20 years.

PICKETT: Not with me.

ELWELL: You overestimate both of us.

Miss Pickett joins Elwell in his office and the door remains open as the medical professor begins quizzing Miss Pickett about whether she knew a man named Praetorius in her hometown of Goose Creek. Yes, Pickett says, "He was a doc.…He healed people," Dr. Elwell asks how he did that. "If I knew how I'd be a doc myself," she replies, telling Elwell that he saved her grandmother. Elwell assumes that the old woman must have passed by now, but Miss Pickett says she's still alive. He asks her grandmother's age. "103, but I think she's lying," Pickett responds. "She's 108 if she's a day." She tells Elwell that her grandmother lay down to die four times and each time, Dr. Praetorius got her back up on her feet. Elwell inquires about the methods of this "miracle man." "Well, some healers use one thing, some use another, but Doc Praetorius used 'em all," she tells him. Elwell shows her a book of faculty members and points to a photo of Praetorius (our first glimpse of Grant) and Pickett positively identifies him, though she says he looked younger then. He asks Miss Pickett if Praetorius was a university-trained doctor.

PICKETT: When you say doctor, do you mean school doctor, out of books?

ELWELL: That is precisely what I mean.

PICKETT: Can't say. For my part I wouldn't get caught dead in a room with one of 'em.

ELWELL: Miss Pickett, I am a school doctor, out of books.

PICKETT: That's one reason why the door is open.

A student (George Offerman Jr.) interrupts the meeting to remind the professor that he's late for his anatomy class that Elwell asked Dr. Praetorius to attend. Elwell tells him to deliver the message that he's been

unavoidably delayed. After the student leaves, he asks Miss Pickett what more she knows. Suddenly, Pickett looks around and she shuts the door. "You're a professor. It's hard to make you understand anything that ain't in the books. Well, most of what goes on in the world ain't in books." Elwell's skepticism is quite palpable. He then asks what she knows of a man named Shunderson. "I didn't know very much. Nobody did," she says with a shiver, though she admits they used to call him "The Bat" before she changes the subject, reminding him that Sergeant Canton of the detective agency that found her mentioned Elwell might have a job for her. This is a rare dropped ball in People Will Talk. It's implied that Elwell wants to plant Pickett as a housekeeper to spy on Praetorius, but her character never appears again. We really have no idea where this film is heading at this point. Is it a comedy? A mystery? As usual in a Joseph L. Mankiewicz screenplay, the dialogue comes full of gems, but since it's not an original screenplay, how much originated in the play, though it was written in German?

unavoidably delayed. After the student leaves, he asks Miss Pickett what more she knows. Suddenly, Pickett looks around and she shuts the door. "You're a professor. It's hard to make you understand anything that ain't in the books. Well, most of what goes on in the world ain't in books." Elwell's skepticism is quite palpable. He then asks what she knows of a man named Shunderson. "I didn't know very much. Nobody did," she says with a shiver, though she admits they used to call him "The Bat" before she changes the subject, reminding him that Sergeant Canton of the detective agency that found her mentioned Elwell might have a job for her. This is a rare dropped ball in People Will Talk. It's implied that Elwell wants to plant Pickett as a housekeeper to spy on Praetorius, but her character never appears again. We really have no idea where this film is heading at this point. Is it a comedy? A mystery? As usual in a Joseph L. Mankiewicz screenplay, the dialogue comes full of gems, but since it's not an original screenplay, how much originated in the play, though it was written in German?

As we finally leave Elwell and Miss Pickett, we arrive in the lecture room of Professor Elwell's anatomy class. The infamous Dr. Noah Praetorius stands playing with the class' skeleton with his mysterious friend Shunderson (Finlay Currie) standing behind him. Praetorius keeps moving the jaw of the skull and wonders out loud, "Why should a man die and then laugh for the rest of eternity?" The student who had interrupted Elwell's meeting comes in and the doctor addresses him as Uriah and asks what he knows about Elwell. "He regrets exceedingly that he is unavoidably detained," Uriah tells him. "A meaningless phrase which could signify anything from oversleeping to being arrested for malpractice," Praetorius replies. The doctor walks to a table at the center

of the room where a corpse lies under a sheet. "I would be quite unable to give the lecture you came to hear and I'm not sure you should hear the lecture I'd like to give," Praetorius tells the students who all clamor, fearful he's going to leave without saying anything. Obviously, the doctor's reputation has made him a figure of fascination among the aspiring physicians and they'd be willing to hear him talk about anything. He asks them to get out their notebooks and uncovers the body, which turns out to be that of a very young woman. He gingerly strokes her long brown hair as he explains to the class, "Anatomy is more or less the study of the human body. The human body is not necessarily the human being. Here lies a cadaver. The fact that she was, not long ago, a living, warm, lovely young girl is of little consequence in this classroom. You will not be required to dissect and examine the love that was in her — or the hate. All the hope, despair, memories and desires that motivated every moment of her existence. They ceased to exist when she ceased to exist. Instead, for weeks and months to come, you will dissect, examine and identify her organs, bones,

of the room where a corpse lies under a sheet. "I would be quite unable to give the lecture you came to hear and I'm not sure you should hear the lecture I'd like to give," Praetorius tells the students who all clamor, fearful he's going to leave without saying anything. Obviously, the doctor's reputation has made him a figure of fascination among the aspiring physicians and they'd be willing to hear him talk about anything. He asks them to get out their notebooks and uncovers the body, which turns out to be that of a very young woman. He gingerly strokes her long brown hair as he explains to the class, "Anatomy is more or less the study of the human body. The human body is not necessarily the human being. Here lies a cadaver. The fact that she was, not long ago, a living, warm, lovely young girl is of little consequence in this classroom. You will not be required to dissect and examine the love that was in her — or the hate. All the hope, despair, memories and desires that motivated every moment of her existence. They ceased to exist when she ceased to exist. Instead, for weeks and months to come, you will dissect, examine and identify her organs, bones, muscles, tissues and so on, one by one. These you will faithfully record in your notebooks and when the notebooks are filled, you will know all about this cadaver that the medical profession requires you to know." Following the doctor's introduction, a young lady (Jeanne Crain, one of the wives in Mankiewicz's A Letter to Three Wives) sitting among the students starts to flutter before she falls into the aisle. The students swarm her until Praetorius clears them away, saying, "A group of Cub Scouts would know better than to crowd like this." He asks if she's ever fainted before, but she says no. She says she's feeling better and the doctor gives her a piece of hard candy and asks another female student to escort her to the bathroom to splash some water on her face. Praetorius has grown impatient and decides to leave, bumping into Professor Elwell at the door. Elwell again apologizes for his delay. Praetorius says that Elwell wanted to ask him something about a tumor. "A malignant dysgerminoma," Elwell responds. "Professor Elwell, you are the only man I know who can say 'malignant' the way other people say 'Bingo!'" Praetorius tells his tardy colleague, unaware of Elwell's investigation into his past. The doctor and Shunderson leave with Praetorius' clinic as their destination.

muscles, tissues and so on, one by one. These you will faithfully record in your notebooks and when the notebooks are filled, you will know all about this cadaver that the medical profession requires you to know." Following the doctor's introduction, a young lady (Jeanne Crain, one of the wives in Mankiewicz's A Letter to Three Wives) sitting among the students starts to flutter before she falls into the aisle. The students swarm her until Praetorius clears them away, saying, "A group of Cub Scouts would know better than to crowd like this." He asks if she's ever fainted before, but she says no. She says she's feeling better and the doctor gives her a piece of hard candy and asks another female student to escort her to the bathroom to splash some water on her face. Praetorius has grown impatient and decides to leave, bumping into Professor Elwell at the door. Elwell again apologizes for his delay. Praetorius says that Elwell wanted to ask him something about a tumor. "A malignant dysgerminoma," Elwell responds. "Professor Elwell, you are the only man I know who can say 'malignant' the way other people say 'Bingo!'" Praetorius tells his tardy colleague, unaware of Elwell's investigation into his past. The doctor and Shunderson leave with Praetorius' clinic as their destination.

At this point, a viewer still would be unclear where this story is heading, especially with the added presence of the large, mostly silent Shunderson usually near Praetorius' side. However, once we get to Praetorius' private

clinic, which really functions more like a full-fledged hospital, the plot will start spinning in more directions. As I wrote earlier, I have no familiarity with the Curt Goetz play upon which it was based. Goetz began his career in Germany as a performer in silent films, including one directed by Ernst Lubitsch in 1918. He also began writing plays. In 1939, he went to Hollywood to try to get into filmmaking there, but got frustrated by the system and moved to Switzerland in 1945 (since he was Swiss by birth) and wrote some novels. His play Dr. Praetorius originally was written in Germany in 1934. The first English translation was called How to Die Laughing, was in seven acts and while it has some similarities to People Will Talk, the synopsis sounds quite different and even brings Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson into the tale. In 1949, Goetz co-directed with Karl Peter Gillmann a German-language version called Frauenarzt Dr. Prätorius that sounds exactly like People Will Talk, has Goetz himself playing the title role and is described as a "melodramatic comedy." That's probably as good a description as any of Mankiewicz's People Will Talk, which may be as idiosyncratic a film as he (or Cary Grant for that matter) ever made.

clinic, which really functions more like a full-fledged hospital, the plot will start spinning in more directions. As I wrote earlier, I have no familiarity with the Curt Goetz play upon which it was based. Goetz began his career in Germany as a performer in silent films, including one directed by Ernst Lubitsch in 1918. He also began writing plays. In 1939, he went to Hollywood to try to get into filmmaking there, but got frustrated by the system and moved to Switzerland in 1945 (since he was Swiss by birth) and wrote some novels. His play Dr. Praetorius originally was written in Germany in 1934. The first English translation was called How to Die Laughing, was in seven acts and while it has some similarities to People Will Talk, the synopsis sounds quite different and even brings Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson into the tale. In 1949, Goetz co-directed with Karl Peter Gillmann a German-language version called Frauenarzt Dr. Prätorius that sounds exactly like People Will Talk, has Goetz himself playing the title role and is described as a "melodramatic comedy." That's probably as good a description as any of Mankiewicz's People Will Talk, which may be as idiosyncratic a film as he (or Cary Grant for that matter) ever made.

When we do get to the clinic, we do get more of a sense of what kind of doctor Noah Praetorius is and what the opening title cards meant when they said if he didn't exist, he should. If that were the case in the early 1950s, it's been multiplied exponentially by 2011. No sooner does he walk in the door that he starts getting hit by nurses and other staff with problems. One nurse informs him that a woman about to be discharged wants to take her gall bladder home with her. Praetorius finds that sweet and tells her to let her. The nurse says he knows they don't keep them after they are removed but the doctor guesses that the woman has no idea what her gall bladder looked like so just get another and "send her home happy." A bean counter talks to him about the costs of the hours for the kitchen staff and they should consider cutting back in terms of the patients' food. (That one is out of my life experience where one for-profit hospital I stayed at wanted to get their kitchen staff out early and served horrendous food out of a box for dinner.) Praetorius tells her that he has "the firm conviction that patients are sick people, not inmates." He then checks in on an older patient (Julia Dean) who doesn't look well and obviously is depressed about her condition.

PATIENT: I was thinking it's not much fun when you get old.

PRAETORIUS: It's even less fun if you don't get to be old.

PATIENT: I want to die.

PRAETORIUS: You'd like that, wouldn't you? Lie around in a coffin all day with nothing to do.

A nurse brings the good doctor a report on the final patient of the day and he asks her to show Mrs. Higgins into his office. She enters and it is the woman who fainted in class. Praetorius tells her the good news that

there's absolutely nothing wrong with her and she can continue her studies, at least for a while. She confesses that she's not a medical student. She was just sitting in on the class to see him. Mrs. Higgins, who tells him to call her Deborah, shows signs of relief until Praetorius asks if she'll make a follow-up appointment or would she be getting her own obstetrician. Deborah breaks down, confusing the doctor, until he realizes that while she may be pregnant, he'd been mistaken to assume she was married. He inquires about the father, but she tells him that he's out of the picture. It seems he was called up to serve in Korea, which led to their coupling, and promptly got himself killed soon after arriving overseas. The doctor attempts to calm her, but Deborah isn't just worried about the shame unwed mothers faced at that time but she's convinced the news will kill her father. Praetorius tells her that parents can surprise you and be very understanding when you least expect it. Deborah insists her father is the most gentle, understanding man in the world, but his heart would be unable to take it.

there's absolutely nothing wrong with her and she can continue her studies, at least for a while. She confesses that she's not a medical student. She was just sitting in on the class to see him. Mrs. Higgins, who tells him to call her Deborah, shows signs of relief until Praetorius asks if she'll make a follow-up appointment or would she be getting her own obstetrician. Deborah breaks down, confusing the doctor, until he realizes that while she may be pregnant, he'd been mistaken to assume she was married. He inquires about the father, but she tells him that he's out of the picture. It seems he was called up to serve in Korea, which led to their coupling, and promptly got himself killed soon after arriving overseas. The doctor attempts to calm her, but Deborah isn't just worried about the shame unwed mothers faced at that time but she's convinced the news will kill her father. Praetorius tells her that parents can surprise you and be very understanding when you least expect it. Deborah insists her father is the most gentle, understanding man in the world, but his heart would be unable to take it.

After Praetorius has at least dammed the flow of Deborah's tears, she hastily exits. His receptionist returns and he asks if Deborah made another appointment but she informs her boss that she did not. The words have

barely left her mouth when a shot is heard. Shunderson joins Praetorius in the hallway as does a nurse where they find a sprawled Deborah, derringer in hand. Miss Higgins is rushed into surgery and after much work, appears to be out of danger. Shunderson enters the operating room as Praetorius removes his surgical garb. "It's a good thing that most people don't have the foggiest notion where the heart is," the doctor says. "She missed it by a mile." Shunderson takes that to mean that her suicide attempt failed which Praetorius confirms. "Then she'll try again," Shunderson declares, giving Praetorius pause and a look of concern. At any rate, Miss Higgins will be out for awhile and Praetorius has an appointment to make. As if the doctor didn't have enough on his plate, he's also the conductor for the university's student-faculty orchestra and it's practice night.

barely left her mouth when a shot is heard. Shunderson joins Praetorius in the hallway as does a nurse where they find a sprawled Deborah, derringer in hand. Miss Higgins is rushed into surgery and after much work, appears to be out of danger. Shunderson enters the operating room as Praetorius removes his surgical garb. "It's a good thing that most people don't have the foggiest notion where the heart is," the doctor says. "She missed it by a mile." Shunderson takes that to mean that her suicide attempt failed which Praetorius confirms. "Then she'll try again," Shunderson declares, giving Praetorius pause and a look of concern. At any rate, Miss Higgins will be out for awhile and Praetorius has an appointment to make. As if the doctor didn't have enough on his plate, he's also the conductor for the university's student-faculty orchestra and it's practice night.

Among the members of the orchestra is Praetorius' closest friend on the university's faculty — physics Professor Lyonel Barker (Walter Slezak) — who plays the bass violin in the orchestra, often to Praetorius' frustration. After the practice has finished, Barker asks Praetorius to stay behind because he needs to speak with him.

Despite their playful bickering during rehearsal, Barker asks Noah if he considers him a trusted friend. Of course, Praetorius says. "Therefore I have the right to point out to you that there are occasions when you behave like a cephalic idiot," Barker tells him. He warns Praetorius that he's heard that Professor Elwell has been snooping around his past in the hopes of making a case with the university out of it. Praetorius doesn't seem concerned, but Barker admits that there are things about his past that even he doesn't know. Noah asks the physics professor if he told him everything there was to know about him, would it affect their friendship? Barker says not in the least. Noah pats Barker on the knee. "I know it's not much to have a friend who knows all about you but one who's afraid he's not quite sure, that's worth having," Praetorius smiles. He tells Barker not to worry, but he needs to drop by the clinic to check on a patient but tells his friend to drop by his house for a late supper when he returns from the clinic.

Despite their playful bickering during rehearsal, Barker asks Noah if he considers him a trusted friend. Of course, Praetorius says. "Therefore I have the right to point out to you that there are occasions when you behave like a cephalic idiot," Barker tells him. He warns Praetorius that he's heard that Professor Elwell has been snooping around his past in the hopes of making a case with the university out of it. Praetorius doesn't seem concerned, but Barker admits that there are things about his past that even he doesn't know. Noah asks the physics professor if he told him everything there was to know about him, would it affect their friendship? Barker says not in the least. Noah pats Barker on the knee. "I know it's not much to have a friend who knows all about you but one who's afraid he's not quite sure, that's worth having," Praetorius smiles. He tells Barker not to worry, but he needs to drop by the clinic to check on a patient but tells his friend to drop by his house for a late supper when he returns from the clinic.

With Shunderson's words still echoing in his mind, Praetorius pays a visit to the recovering Deborah and tells her a whopper of a lie. He says they discovered that a lab error accidentally switched labels on two pregnancy tests being run at the same time and hers actually was negative while another woman's was positive. She therefore has no reason to be concerned. It still turns on the waterworks anyway. He asks her why she's crying now, but she says he wouldn't understand. He wishes her goodnight and tells her to rest because she has nothing to worry about now. When he gets home, he tells Barker what he did. The physics professor says he has to know that it's just a stall and she will learn the truth eventually. Noah says that he realizes that, but if he can ease her mind until perhaps he can talk to her father, things will be better. Barker's mind wanders off subject as he raves about how good the sauerkraut is, saying it reminds him of home. Praetorius lets him on his secret: He has his housekeeper make it. "Sauerkraut needs to come from a barrel, not a can," the doctor declares. He promises to send some home

with Barker, but it's taken Praetorius' mind off subject as well to a pet peeve of his. He grabs a stick of paper-wrapped butter. "Our American mania for sterile packages has removed the flavor from most of our foods. Butter is no longer sold out of wooden buckets and a whole generation thinks butter tastes like paper," Praetorius complains. "There was never a perfume like an old-time grocery store. Now they smell like drug stores which don't even smell like drug stores even more." Before his tirade can go much further, the phone rings. It's the night matron at the clinic (Maude Wallace). It seems that Deborah has disappeared. She tells the doctor she doesn't know how she slipped out. Praetorius tells her that she probably walked past her and out the front door just as he did about an hour ago. When he hangs up, Barker guesses that the missing patient is the one that Noah lied to and now the doctor finds himself in a bit of a quandary.

with Barker, but it's taken Praetorius' mind off subject as well to a pet peeve of his. He grabs a stick of paper-wrapped butter. "Our American mania for sterile packages has removed the flavor from most of our foods. Butter is no longer sold out of wooden buckets and a whole generation thinks butter tastes like paper," Praetorius complains. "There was never a perfume like an old-time grocery store. Now they smell like drug stores which don't even smell like drug stores even more." Before his tirade can go much further, the phone rings. It's the night matron at the clinic (Maude Wallace). It seems that Deborah has disappeared. She tells the doctor she doesn't know how she slipped out. Praetorius tells her that she probably walked past her and out the front door just as he did about an hour ago. When he hangs up, Barker guesses that the missing patient is the one that Noah lied to and now the doctor finds himself in a bit of a quandary.

Now as you probably can ascertain, as usually happens in films of this period and earlier, romance sparks insanely fast between Deborah and Noah, though to the film's credit you can't be certain at first if Praetorius truly has fallen for Deborah or if he simply proposes to her as a way of saving her reputation and rescuing her father Arthur (Sidney Blackmer) who lives under the thumb of his ultraconservative brother John (Will Wright) on his farm. Mr. Higgins describes himself as "an indifferent journalist, a minor poet, an ineffective teacher, a wretched businessman unable to provide for my wife and my child and then not even for my child" who ended up as his brother's dependent. In another classic Mankiewicz exchange after Praetorius has heard about all he can from Deborah's Uncle John, he and Deborah's father share this dialogue.

PRAETORIUS: How old were you when you learned to walk?

ARTHUR: I did pretty well by the time I was 4.

PRAETORIUS: When did you leave the farm?

ARTHUR: When I was 16.

PRAETORIUS: It couldn't have taken you 12 years to make up your mind.

We've got several plates spinning in the air now: A sudden marriage, a pregnant woman who doesn't know she's pregnant, a mysterious man, a professor secretly crusading against a popular doctor — no wonder if you peruse reviews written recently or when People Will Talk came out in 1951, many scratch their head because

it doesn't fall into any standard formula. People criticize it for not being a good romance, but that's the weakest element and least interesting part of what's going on here. Praetorius admits to Deborah that he didn't marry her just to stop her from committing suicide and to save her reputation because that wouldn't be a very practical solution should a similar case arise. He can't marry all his patients. Deborah also finds the reality of the man once she lives with him and for his 42nd birthday buys him an elaborate toy train set which he sets up with her father running a line from one bedroom, Barker from another and Noah serving as chief conductor in another. Of course, there's a spectacular crash causing the three men to yell at each other and it coincides with the delivery of a message from Professor Elwell that the dean is assembling a hearing of faculty members to hear charges against Praetorius (set for the same night as the big orchestra concert no less). Deborah goes to their bedroom and collapses to the bed in tears. Noah assumes she's upset about the letter but she tells him, "It's just that I love you so much and I went and put all those candles on that cake when you're really only 9-years-old."

it doesn't fall into any standard formula. People criticize it for not being a good romance, but that's the weakest element and least interesting part of what's going on here. Praetorius admits to Deborah that he didn't marry her just to stop her from committing suicide and to save her reputation because that wouldn't be a very practical solution should a similar case arise. He can't marry all his patients. Deborah also finds the reality of the man once she lives with him and for his 42nd birthday buys him an elaborate toy train set which he sets up with her father running a line from one bedroom, Barker from another and Noah serving as chief conductor in another. Of course, there's a spectacular crash causing the three men to yell at each other and it coincides with the delivery of a message from Professor Elwell that the dean is assembling a hearing of faculty members to hear charges against Praetorius (set for the same night as the big orchestra concert no less). Deborah goes to their bedroom and collapses to the bed in tears. Noah assumes she's upset about the letter but she tells him, "It's just that I love you so much and I went and put all those candles on that cake when you're really only 9-years-old."

I think the reason People Will Talk confuses so many people comes down to three main factors: 1) Expectations for a Joe Mankiewicz film based on A Letter to Three Wives and All About Eve; 2) Expectations for a Cary Grant movie; and 3) Viewers lumping their own ideological baggage onto the film. With his two previous films, Mankiewicz truly established himself as a master of sharp, witty dialogue and that's present again in People Will Talk, only it doesn't always take the form of comedy. He has some points

to make and I think that makes some feel uneasy, especially since the opening scene between Hume Cronyn and Margaret Hamilton sets the audience up to expect another pure comedy is on the way. When we switch to the anatomy class, though there are laughs to be found, he's subtly switching the tone to be more multi-faceted, particularly when he speaks of the cadaver's former life. By the time we get to the clinic, he's driven the point home that different approaches to medicine are what he's after here. It shouldn't have been a surprise: That's why I used the screenshots of those two title cards that start the film to start the post. There was a third, praising doctors in general, but given some of the doctors I've run across in my hellish journey through the health care system, that title card reads as hopelessly out of date because while there are good doctors today there also are a lot of greedy and incompetent bastards who don't give a shit as well. People Will Talk often is called ahead of its time because of its treatment of Deborah's out-of-wedlock pregnancy, but what really makes the film prophetic is how it pits Dr. Praetorius' commitment to healing the patient as the priority above everything else while doctors such as Professor Elwell want less to do with them and accountants try to cut costs on things such as food service for hospitals. This was made 60 years ago and it's only worse now. Imagine if the issues of billing and health insurance came into play.

to make and I think that makes some feel uneasy, especially since the opening scene between Hume Cronyn and Margaret Hamilton sets the audience up to expect another pure comedy is on the way. When we switch to the anatomy class, though there are laughs to be found, he's subtly switching the tone to be more multi-faceted, particularly when he speaks of the cadaver's former life. By the time we get to the clinic, he's driven the point home that different approaches to medicine are what he's after here. It shouldn't have been a surprise: That's why I used the screenshots of those two title cards that start the film to start the post. There was a third, praising doctors in general, but given some of the doctors I've run across in my hellish journey through the health care system, that title card reads as hopelessly out of date because while there are good doctors today there also are a lot of greedy and incompetent bastards who don't give a shit as well. People Will Talk often is called ahead of its time because of its treatment of Deborah's out-of-wedlock pregnancy, but what really makes the film prophetic is how it pits Dr. Praetorius' commitment to healing the patient as the priority above everything else while doctors such as Professor Elwell want less to do with them and accountants try to cut costs on things such as food service for hospitals. This was made 60 years ago and it's only worse now. Imagine if the issues of billing and health insurance came into play.

By 1951, Cary Grant had been a star for a long time so most moviegoers had come to expect a certain type of role from him. Whether it be a fast-talking smoothie in a screwball comedy such as His Girl Friday, a more

refined romancer in The Philadelphia Story, an adventurer in Gunga Din, a serious romantic with a mission that takes precedence in Notorious or even a fretful father in the weepy Penny Serenade, he always seemed to be in charge or at least care about the outcome. The only possible exception would be Bringing Up Baby where he's at Katharine Hepburn's mercy. As Praetorius, he certainly goes above and beyond when it comes to caring about his patients, but he plays the doctor at a distance from the audience, something quite unusual for him, and Praetorius seems indifferent to the investigation by Elwell. The real switch, which really I can only think of happening in Baby, is that Deborah figures out rather quickly what he's up to when he pursues her at the farm and she starts stalking him around the dairy. It's unusual to see Cary Grant be the prey and it’s to Jeanne Crain’s credit that she makes Deborah’s transition believable. Grant gave a lot of great performances and is one of Oscar's biggest crimes that he only was nominated twice, both for tear jerkers. While I love Walter Burns, I have to admit that Dr. Noah Praetorius might be the best work he ever did on film.

refined romancer in The Philadelphia Story, an adventurer in Gunga Din, a serious romantic with a mission that takes precedence in Notorious or even a fretful father in the weepy Penny Serenade, he always seemed to be in charge or at least care about the outcome. The only possible exception would be Bringing Up Baby where he's at Katharine Hepburn's mercy. As Praetorius, he certainly goes above and beyond when it comes to caring about his patients, but he plays the doctor at a distance from the audience, something quite unusual for him, and Praetorius seems indifferent to the investigation by Elwell. The real switch, which really I can only think of happening in Baby, is that Deborah figures out rather quickly what he's up to when he pursues her at the farm and she starts stalking him around the dairy. It's unusual to see Cary Grant be the prey and it’s to Jeanne Crain’s credit that she makes Deborah’s transition believable. Grant gave a lot of great performances and is one of Oscar's biggest crimes that he only was nominated twice, both for tear jerkers. While I love Walter Burns, I have to admit that Dr. Noah Praetorius might be the best work he ever did on film.

Now little can be done to control what people think they see in things. We live in a world where TV preachers thought certain Teletubbies were gay for crying out loud. Admittedly, the film does have some unmistakably liberal viewpoints, particularly in the scenes where Uncle John spouts his views at the farm, but I think far too

many people mistake Professor Elwell's campaign against Praetorius as some sort of metaphor for McCarthyism. (This was based on a play originally written in Germany in 1934 after all.) People Will Talk's only concern is comparing medical philosophies. Elwell's only interested in one admittedly unusual faculty member who has an odd friend who always stands by his side. I won't give away the details of the hearing because I want more people to see this movie. It's not a perfect movie and it's certainly no All About Eve, but I think it's better than A Letter to Three Wives and I like that film a lot. The performances across the board are great and that sparkling Mankiewicz dialogue is as quotable as ever. Time and again I'm amazed how many early films addressed problems with our health care system in different ways such as 1931's Night Nurse and Mankiewicz's own No Way Out the year before, even though racism was its bigger issue. The Brits even exposed their own failings in 1938's The Citadel before they reformed their system. We in the U.S. should be ashamed. I think one great quote that Praetorius delivers during his hearing proves particularly prescient.

many people mistake Professor Elwell's campaign against Praetorius as some sort of metaphor for McCarthyism. (This was based on a play originally written in Germany in 1934 after all.) People Will Talk's only concern is comparing medical philosophies. Elwell's only interested in one admittedly unusual faculty member who has an odd friend who always stands by his side. I won't give away the details of the hearing because I want more people to see this movie. It's not a perfect movie and it's certainly no All About Eve, but I think it's better than A Letter to Three Wives and I like that film a lot. The performances across the board are great and that sparkling Mankiewicz dialogue is as quotable as ever. Time and again I'm amazed how many early films addressed problems with our health care system in different ways such as 1931's Night Nurse and Mankiewicz's own No Way Out the year before, even though racism was its bigger issue. The Brits even exposed their own failings in 1938's The Citadel before they reformed their system. We in the U.S. should be ashamed. I think one great quote that Praetorius delivers during his hearing proves particularly prescient.

"The issue is whether the practice of medicine will become more intimately involved with the human being it treats or whether it is to continue to go on in its present way to become more and more a thing of pills, serums and knives until it eventually will undoubtedly evolve an electronic doctor."

Honestly, given some of the M.D.s I've encountered, I'm not so sure an electronic doctor would be worse. I do know though that what makes me like People Will Talk more each time I see it falls along the same lines as many new films that captivate me: They dare to be different and to eschew formula while employing talented casts to tell unusual stories well.

Tweet

Labels: 50s, Cary, Cronyn, John Ford, K. Hepburn, Lubitsch, Mankiewicz, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Poitier, Widmark

Comments:

<< Home

This is one of the great underrated films of the 50s - it's a quirky little gem, and I'm not quite sure why it hasn't been rediscovered by the multitudes as of this writing; if "flops" like Bringing Up Baby and The Night of the Hunter can be belatedly recognized as classics, I'm not sure why time hadn't caught up with People will Talk...one can only hope that, eventually, it does. While I wouldn't go so far as to call this Grant's best performance (he's wonderful in it, but I have to give a few other entries on his resume preference), it's certainly one of his more daring ones - it's difficult to make a very literary-seeming character like this credible, and more difficult still to make him entirely likeable, but Grant keeps everything in balance and embodies the contradictions of the role beautifully. Crain certainly did well by Mankewicz - by the writer-director's own admission, she was not the greatest of actresses (Fox foisted her upon him on several occasions - only once, when she was suggested for the role of Eve Harrington, did he balk), but she clearly responded well to his direction, and he drew career-best performances from her; the Best Actor category was fairly competitive in 1951, but the Best Actress category certainly wasn't (it took two supporting performances just to fill out the slate), and I do think both Grant and Crain belonged in those line-ups. I also really love the supporting performances of Hume Cronyn and, most especially, Finlay Currie, whose 11th hour "confession" speech is one of the highlights of the film for me. Thanks for this tribute, Ed - it makes me watch People will Talk again, and will hopefully prompt many of your readers to sample it for the first time.

Oh my goodness, I love this post! I never knew there are other people who love People Will Talk. I love that movie so much. Not just because of Cary Grant. Or maybe because I still have that idealistic view. But I believe that there are still people like Dr. Praetorius.

Post a Comment

<< Home