Wednesday, January 16, 2008

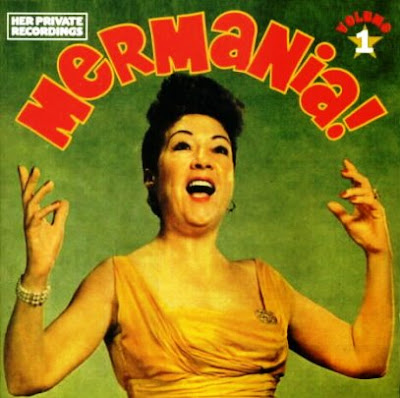

Centennial Tributes: Ethel Merman

By Josh R

Stephen Sondheim tells a great story about Ethel Merman — it draws laughs when he repeats it at speaking engagements, although it must have been hard to find much humor in the event in question when it originally occurred. For those whose knowledge of the musical theater doesn’t extend much beyond the recent film adaptations of Hairspray and Dreamgirls, a bit of background information may be required:

Along with composer Jule Styne and bookwriter Arthur Laurents, Sondheim had created a musical based on the memoirs of Gypsy Rose Lee, the celebrity stripper who had been pushed, prodded and essentially bullied into show business by her domineering mother, Rose Hovick — the kind of stage parent who could vaporize her children's rivals with as little as a withering stare. The show was conceived as a vehicle for its star; it

was Merman, in fact, who had put the kibosh on the idea of Sondheim penning the score for Gypsy in addition to its lyrics (nervous about the prospect of putting her fate in the hands of an untested composer, she insisted on the involvement of someone more experienced). Since the idea of Ethel playing a stripper was appealing to absolutely no one — she was built rather like a defensive linebacker — the part of the mother was built up into the star role. As conceived by Laurents and Sondheim, it amounted to a complex, multifaceted character study with enough psychological wrinkles built into it to keep a team of Freudian scholars intrigued for years. The real Rose had been something of a monster, with behavior ranging from moderately abusive to downright sadistic. While Lee had soft-pedaled the more repellent aspects of her mother’s character in her autobiography, the peculiar forces that drove Mama — a relentless, monolithic ambition to make her daughters into stars, the need to experience vicarious fulfillment through their success, and the barely suppressed rage of someone all too achingly aware of her own lost opportunities — were still present and accounted for.

was Merman, in fact, who had put the kibosh on the idea of Sondheim penning the score for Gypsy in addition to its lyrics (nervous about the prospect of putting her fate in the hands of an untested composer, she insisted on the involvement of someone more experienced). Since the idea of Ethel playing a stripper was appealing to absolutely no one — she was built rather like a defensive linebacker — the part of the mother was built up into the star role. As conceived by Laurents and Sondheim, it amounted to a complex, multifaceted character study with enough psychological wrinkles built into it to keep a team of Freudian scholars intrigued for years. The real Rose had been something of a monster, with behavior ranging from moderately abusive to downright sadistic. While Lee had soft-pedaled the more repellent aspects of her mother’s character in her autobiography, the peculiar forces that drove Mama — a relentless, monolithic ambition to make her daughters into stars, the need to experience vicarious fulfillment through their success, and the barely suppressed rage of someone all too achingly aware of her own lost opportunities — were still present and accounted for. Sondheim had conceived of a pivotal moment during the show-closing number “Rose’s Turn,” a climatic soliloquy in which the character’s roiling emotions came bubbling to the surface in what amounted to a mental meltdown set to music. Toward the end of the song, Rose — who is exorcising the accumulated grief, anger and disappointment of 50-odd years — gets to the point where she is reduced to stammering. Sondheim was inspired by seeing Jessica Tandy in Elia Kazan’s legendary production of A Streetcar Named Desire; as Blanche DuBois, Tandy began tripping over her words in helpless, babbling hysteria once the character’s sanity had irrevocably deteriorated. In Gypsy, Merman was to struggle with the word “Mama”. In the script, it appeared as “M-m-m-mama, M-m-m-mama.”

When it came time to rehearse the scene, Merman had one question. “Here, where it says M-m-m-mama, with the stutterin’….d’ya want that on a upbeat or a downbeat?”

Sondheim and Laurents stared at her incredulously. It was carefully explained to Merman that “the stutterin’” represented a moment of extreme emotional distress, during which the character was literally fighting to get her words out. Not only was she confronting the harsh realities of an entire existence spent observing from the sidelines, but her daughter’s ultimate rejection of her awakens dormant memories of Rose’s abandonment by her own mother.

Merman listened stone-faced, her blank expression unchanging, while her director and the lyricist patiently outlined the character’s fragile emotional state and the significance of the peculiar speech pattern. When their detailed presentation had reached its conclusion, she offered this in response:

“So didja want that on an upbeat or a downbeat?”

At that moment, Sondheim realized that while he had fought the good fight, there was little point in persevering — “Do it on an upbeat, Ethel,” he responded in weary resignation. Great entertainers are not necessarily great actors, just as the reverse is often frequently the case. For better or worse, Merman was Merman, and tutoring her on the basics of character development had about as much practical utility as there would have been in stationing Jessica Tandy downstage center to belt out “Everything’s Coming Up Roses.”

Unlike film, the stage is not a permanent record; instances of performers attaining legendary status solely for their work in the theater are few and far between. It takes

a big talent — and an even bigger personality — to make an impression so forceful that their accomplishments not only stand the test of time, but define a style of performance so completely that it becomes their legacy. It is doubtful that Merman made any kind of study of the tenets of “method” acting; if the name Stanislavski had come up in conversation, she might be forgiven for mistaking it for that of the maitre'd at The Russian Tea Room. She was not an intellectual — nor, by all accounts, was she naturally curious. Really, there is nothing to suggest that she was even remotely interested in the complexities of human behavior, at least as far as her work was concerned (she infamously made a bargain with Jerry Orbach, with whom she worked in the 1966 revival of Annie Get Your Gun, that if he wouldn’t react to her performance, she wouldn’t react to his.) What she had was a clarion voice, as pure and as powerful as an entire brass section, a killer sense of comic timing, and an intuitive understanding of what it took to hold an entire audience in the palm of her hand. People flocked to her performances with the expectation of seeing a force of nature in action; for her part, Merman saw no reason to do anything other than plant her two little feet on the edge of that stage, and let 'em have it.

a big talent — and an even bigger personality — to make an impression so forceful that their accomplishments not only stand the test of time, but define a style of performance so completely that it becomes their legacy. It is doubtful that Merman made any kind of study of the tenets of “method” acting; if the name Stanislavski had come up in conversation, she might be forgiven for mistaking it for that of the maitre'd at The Russian Tea Room. She was not an intellectual — nor, by all accounts, was she naturally curious. Really, there is nothing to suggest that she was even remotely interested in the complexities of human behavior, at least as far as her work was concerned (she infamously made a bargain with Jerry Orbach, with whom she worked in the 1966 revival of Annie Get Your Gun, that if he wouldn’t react to her performance, she wouldn’t react to his.) What she had was a clarion voice, as pure and as powerful as an entire brass section, a killer sense of comic timing, and an intuitive understanding of what it took to hold an entire audience in the palm of her hand. People flocked to her performances with the expectation of seeing a force of nature in action; for her part, Merman saw no reason to do anything other than plant her two little feet on the edge of that stage, and let 'em have it. The woman destined to become known, both affectionately and otherwise, as “The Merm,” was born Ethel Agnes Zimmerman in Astoria, Queens on Jan. 16, 1908. She worked as a secretary for the B-K-Booster Vacuum Cleaner Company before embarking on a career in vaudeville. Her Broadway debut came with a featured role in Gershwin’s 1930 Girl Crazy — while a 19-year-old named Ginger Rogers was the alleged star of the production, it was Merman who set Broadway on its ear. The high point of her performance came during her rendition of “I Got Rhythm,” in which she held a C-note for 16 earth-shattering bars. The audience went berserk, demanding multiple encores — as the proverb goes, a star was born.

Cole Porter was to become her greatest champion over the course of the next decade; all together, they collaborated on six productions, mostly hits. If it seemed like an unlikely union — the urbane sophisticate and the brass-lunged belter — Merman’s earthy forcefulness brought an element of substance to the material, which was often whimsical if not wispy in nature. Anything Goes was her first leading role, and a roaring success; audiences responded to her vocal virtuosity and her take-no-prisoners approach to putting over a number. Subsequent hits included Red, Hot and Blue and Something for the Boys, both opposite Jimmy Durante, and two genuine smashes — DuBarry Was a Lady, in which she and Bert Lahr routinely stopped the show with the comic duet “Friendship,” and Panama Hattie. In the late 1940s, she began her association with Irving Berlin, who provided the star with her two best vehicles to date. Annie Get Your Gun, a highly fictionalized account of the life and loves of legendary sharp-shooter Annie Oakley, was about as close to perfection as a musical can get; a big, jubilant glorification of a mythological Wild West that never was, and with nary a bad song in it, it fashioned Merman with what was to become her signature song, “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” Call Me Madam, which cast her in a tailor-made role as a brassy society hostess appointed ambassador to a fictional European nation, was almost as good, and won her the Tony Award. After announcing her intention to retire after Gypsy, she reprised her role in the 1966 Broadway revival of Annie Get Your Gun — referred to by theater insiders as “Granny Get Your Gun”. It didn’t matter that she was nearly 60 years old at the time; her voice remained as strong and clear as it always had, and audiences happily bought into the illusion. She closed out the storied run of Hello, Dolly!, winning a special Drama Desk Award for a role she had originally taken a pass on.

For all the success that Merman had on the stage — and not even her chief rival, Mary Martin, really came close to matching her track record — her film career never really got off the ground. It went beyond the fact that Merman was not, to put it delicately, attractive in the conventional sense or particularly photogenic. The camera doesn’t lie, and what works on a stage doesn’t necessarily translate onto the screen — film is fundamentally an actor’s medium, not an entertainer’s. In close-up, it was apparent how limited Merman’s dramatic skills were, and the extent to which she was dependent on a live audience to work her special brand of magic. Call Me Madam and a radically reworked version of Anything Goes (which had Ethel playing second banana to Bing Crosby) were the only two of her Broadway triumphs which she repeated on film. Panama Hattie and DuBarry were assigned by MGM to two non-singers, Ann Sothern and Lucille Ball, while Judy Garland was replaced on Annie Get Your Gun by Betty Hutton. In a way, this last piece of casting must have been more galling to Merman than the others. Hutton had played a secondary role in the original 1939 production of Panama Hattie — the fact that she was cited as a scene-stealer by many critics did not sit particularly well with the show’s leading lady.

The loss of her lead role in the film adaptation of Gypsy, undoubtedly the greatest triumph of her career, to Rosalind Russell was particularly painful, if arguably justified. On stage, the role may have required a great singer more than it needed a great actress, but on film, the opposite may have well proved the case (it has been suggested that the reason she lost the Tony to Mary Martin, who won for The Sound of Music, was that she didn’t quite do the role justice from an acting standpoint). What remained of Merman’s film career was eclectic, to say the least. She was stranded on a desert island with Crosby, Carole Lombard, George Burns and Gracie Allen in We’re Not Dressing, a bizarre curio of the early '30s, and had a small role in Alexander’s Ragtime Band. 1954’s There’s No Business Like Show Business was a splashy, trashy 20th Century Fox musical which seemed more interested in Marilyn Monroe than it was with Merman. Her best film performance came, rather predictably, with a one-note role in the raucous ensemble comedy It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; she played the shrill archetype of the monstrous mother-in-law for what it was worth, and was the only woman in the film to make any kind of impression. Fans of the 1980 cult classic Airplane! would have my head if I didn’t make some mention of her brief cameo as the soldier suffering from head injuries who believes himself to be Ethel Merman. Her Lieutenant Hurwitz has to be strapped down and sedated to be stopped from belting out “Everything's Coming Up Roses” — a fitting metaphor for the irrepressible energy and drive of a woman who believed, above all other things, that the show must go on.

Behind the talent, the triumphs, and the legend lies the story of a woman whose personality was just as forceful offstage as it was on. She was, by common consensus, a vulgar, overbearing figure whose consummate professionalism didn’t necessarily allow

for a spirit of generosity, or camaraderie with others. It's possible that she made more enemies than friends during her four decades as a star; her co-workers frequently described her in less than flattering terms. Sondheim referred to her as “The Talking Dog” — possibly in reference to her acting ability, but certainly a reflection of the mutual animosity that existed between them. Fernando Lamas, her leading man in the 1955 Broadway musical Happy Hunting, likened kissing her to “kissing a truck driver,” and made a point of ostentatiously wiping his mouth with the back of his hand during one performance to drive the point across; Merman filed a complaint with Actors Equity over the incident, and her co-star was forced to issue a formal apology and pay a fine. Her personal life was no less without its share of unpleasantness and intrigue. A chapter of her autobiography entitled “Ernest Borgnine,” in reference to her marriage to the Oscar-winning actor (which ended in a hasty annulment after 32 days), consisted of one blank page. As a mother, she may or may not have been a more nurturing presence than Rose Hovick; her only daughter died of a drug overdose, which the star firmly stipulated was not a suicide. There was no end to speculation surrounding her sexual orientation, although this seemed to be more a product of rumor than a reflection of genuine fact. It is known that her friendship with pulp novelist Jacqueline Susann ended with an acrimonious falling-out, although there is little hard evidence to support the claim that they were ever romantically involved. There was an element of malice involved with these rumors — while many of her detractors charged her with being “unfeminine,” she made some enemies in the gay community with what were ocassionally perceived as homophobic attitudes.

for a spirit of generosity, or camaraderie with others. It's possible that she made more enemies than friends during her four decades as a star; her co-workers frequently described her in less than flattering terms. Sondheim referred to her as “The Talking Dog” — possibly in reference to her acting ability, but certainly a reflection of the mutual animosity that existed between them. Fernando Lamas, her leading man in the 1955 Broadway musical Happy Hunting, likened kissing her to “kissing a truck driver,” and made a point of ostentatiously wiping his mouth with the back of his hand during one performance to drive the point across; Merman filed a complaint with Actors Equity over the incident, and her co-star was forced to issue a formal apology and pay a fine. Her personal life was no less without its share of unpleasantness and intrigue. A chapter of her autobiography entitled “Ernest Borgnine,” in reference to her marriage to the Oscar-winning actor (which ended in a hasty annulment after 32 days), consisted of one blank page. As a mother, she may or may not have been a more nurturing presence than Rose Hovick; her only daughter died of a drug overdose, which the star firmly stipulated was not a suicide. There was no end to speculation surrounding her sexual orientation, although this seemed to be more a product of rumor than a reflection of genuine fact. It is known that her friendship with pulp novelist Jacqueline Susann ended with an acrimonious falling-out, although there is little hard evidence to support the claim that they were ever romantically involved. There was an element of malice involved with these rumors — while many of her detractors charged her with being “unfeminine,” she made some enemies in the gay community with what were ocassionally perceived as homophobic attitudes.

Whatever people felt about her, either as an actress or an individual, there was no denying the power and the impact of what she accomplished onstage. Her performance on the original cast recording of Gypsy represents something that will never be duplicated or equaled — it is, quite simply, the greatest vocal interpretation of a role ever captured in sound. You can hear Merman’s influence to this very day — on Broadway, community and high school stages in this country and around the world. When Idina Menzel belted out “Defying Gravity” on the 2004 Tony Awards — transforming a power ballad into a vocal tour-de-force through shear physical stamina, practically muscling the song into submission — you could all but see the ghost of Ethel Merman hovering overhead, nodding in motherly approval. The truth was that Merman didn’t need to be a great actress; she was less concerned with complexity of characterization than with the act of giving a performance. That meant giving something to the audience who came for the purpose of witnessing a once-in-a-lifetime event. Merman felt the obligation to deliver such an experience very keenly, and she always gave it her all. As the song says, who could ask for anything more?

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Borgnine, Cole Porter, Garland, Ginger Rogers, Kazan, L. Ball, Lombard, Marilyn, Merman, Musicals, Orbach, Roz Russell, Sondheim, Tandy, Theater

Comments:

<< Home

Aw, Josh R.! You mentioned Airplane for Ed, but nothing for me! You could have mentioned Ethel's horrific Friendship cottage cheese commercial (I thought she was saying "It's Frien-Shit! Frien-Shit!" when I was a kid), or her infamous disco album! Or her appearance on The Muppet Show, where she sang "You're The Top" with Kermit.

But you covered so many other good things in your piece that I shouldn't complain. I learned some new and interesting things about Merman.

But you covered so many other good things in your piece that I shouldn't complain. I learned some new and interesting things about Merman.

I've said it before and I've said it again: If time travel were possible, one of my first stops would be to see Merman play Mama Rose live on stage.

I'm late to this party -- great tribute to Merman. Just one note: Ann Sothern was NOT a non-singer, as her fine recording of "Lady in the Dark," based on an early 50's TV production, will attest to. She also starred in the original Broadway production of "Of Thee I Sing."

She was a force of nature with a one of a kind voice. I don't think she was "butch", just not conforming to the Hollywood cookie cutter mold of the day... For better or worse, she was true to herself. That's why we still remember the great "Merm"!!

Marie Pea

Post a Comment

Marie Pea

<< Home