Saturday, October 14, 2006

A musical with more cats than CATS

By Josh R

You may or may not know that Broadway is, in fact, the longest residential street in the world. It extends from the southern tip of Manhattan 150 miles north to Albany, N.Y., where it comes to quiet halt, incongruously flanked by modestly apportioned tract houses with neatly groomed lawns…a far cry from the glittering, gaudy majesty of Times Square. In truth, Broadway's reach extends much further than that — all the way to the soundstages of Hollywood, California. For much of the 20th century, The Dream Factory took its cues from The Great White Way, often plundering some of its greatest successes for film adaptation. Many of the most beloved movie musicals ever made — including best picture winners West Side Story, My Fair Lady and The Sound of Music — began their lives on Broadway.

In recent years, however, a curious phenomenon has begun to take shape, as the two entities have enjoyed an increasingly reciprocal relationship. Just as Hollywood continues to turn stage hits into films — Chicago, Rent, The Phantom of the Opera, and the upcoming Dreamgirls, to cite a few recent examples — so has Broadway begun adapting successful films into stage musicals. Four of the last nine Tony Award winners for best musical are based on feature films — The Lion King, The Producers, Hairspray and Spamalot, the last of an adaptation of Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Grey Gardens, which began previews at the Walter Kerr Theatre on Oct. 3 in anticipation of a Nov. 2 opening, is the latest example of this growing trend, albeit one with a curious twist. This musical draws its inspiration not from a scripted fiction-based film, but from a documentary. It is the first (and is likely to stand as the only) instance of a documentary being used as the basis of a Broadway musical.

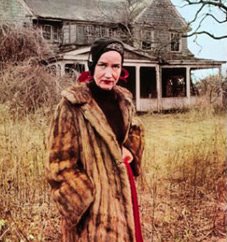

The film, which has acquired a cult standing since its premiere in 1975, examines the fallen fortunes of two women, both named Edith Bouvier Beale — an eccentric mother and daughter who inhabit the titular estate. Since they share a name, they distinguish themselves as Big and Little Edie, respectively. Their celebrity standing, as far as the outside world is concerned, owes itself to family connections — Big Edie is the aunt of Jacqueline (Bouvier) Kennedy Onassis. Once well-regarded members of the social elite, by the early '70s the two women were discovered living an impoverished, isolated existence in Grey Gardens, a dilapidated 28-room Easthampton mansion overrun by more than 50 stray cats and an assortment of raccoons; judging by the looks of things, the term "squalor" only barely scratches the surface. The New York Board of Health had authorized a survey of the house, once considered a showplace, and subsequently declared it to be "unfit for human habitation" as a result of their findings. The media coverage surrounding these events prompted an eventual, if somewhat shamefaced, intervention by an embarrassed Mrs. Onassis. Although long-estranged from her black-sheep relations, she dispatched a task force of construction workers and pest-control experts to Long Island to get the mansion (barely) back up to code to forestall condemnation of the property and the eviction of its tenants. Even more significantly, filmmakers Albert and David Maysles were motivated to track down the reclusive pair, and film them over a period of months.

The film is an oddity, alternately shocking, touching, and mordantly humorous in its consideration of two larger-than-life eccentrics living on the margins of society. The musical, which I saw in its off-Broadway premiere at Playwrights Horizons last spring, attempts to provide some context for the women's behavior, giving a glimpse of what their lifestyle was before it all came apart at the seams. The first act takes place in the summer of 1941, when Grey Gardens is at the peak of its splendor and WWII is still just a rumble on the horizon. Prominent socialite Edith Bouvier Beale, played by Christine Ebersole, is preparing an elaborate party at her Long Island estate to celebrate her daughter's engagement to Joseph Kennedy Jr. (the younger incarnation of the daughter was played by Sara Gettelfinger at Playwrights Horizons, and has been replaced by Erin Davie for the Broadway production). Mother and daughter have a complicated and often contentious relationship, exacerbated by the fact that both are natural "performers" competing for the spotlight and the attentions of a physically (and emotionally) absent husband/father. Subconsciously afraid of being abandoned, Big Edie eventually sabotages the relationship between her daughter and her fiance, and the engagement is dissolved. Little Edie resolves to leave Grey Gardens, but her attempts to extricate herself from the role of her mother's keeper are ultimately doomed to failure.

The second act picks up where the documentary begins — with Ebersole switching gears to take on the role of the daughter, while Mary Louise Wilson assumes the role of the mother — and follows the action of the film very closely. Big Edie, now a bedridden, 80-year-old harridan munching on cat food, fondly recalls her days as a prominent socialite and would-be opera singer while singing along in a shrill voice to ancient gramophone recordings. 56-year-old Little Edie, a one-time debutante who counted Howard Hughes, Nelson Rockefeller and John Paul Getty among her suitors, now drifts through the abandoned rooms in a variety of outlandishly bizarre garments (fashioned out of materials as unlikely as duvet covers and old curtains) recounting her triumphs and disappointments to the odd visitor in breathless, stream of-consciousness fashion. Nursing old wounds that never fully healed, the two women seem suspended in a sort of existential limbo where time has little meaning — their sanity eroded by years of neglect and thwarted ambitions, they squabble over decades-old slights and conflicting versions of their shared history. Their relationship is contentious, but not without love — forged in co-dependency, it makes them protective of one another even when airing their resentments.

If this all sounds rather strange, it is, really. But truth, as they say, is often stranger than fiction, and the musical successfully captures the essence of the film, highlighting the absurdity of its outrageous subjects without reducing them to caricatures — which would have been the obvious temptation given how easily the material might lend itself to Grand Guignol (or worse, full-on camp). If the show falls short in certain respects — it does feel like two very different musicals awkwardly shoehorned into one — it is a beautifully mounted production, masterfully directed by Michael Greif (Rent), with an excellent score by newcomers Scott Frankel and Michael Korie. Doug Wright's libretto feels oddly stilted in the first act, but flows more naturally in the second when adhering directly to the dialogue from the film. What really distinguishes the production is the performance of Christine Ebersole, giving twin tour-de-forces in two very different roles which collectively give full expression to the broad spectrum of her talents.

Through far from a household name, the actress has worked regularly since the late 1970s, achieving a moderate degree of recognition as a character actress in television and film. For the first 20 years or so, she seemed like a talent in search of a home — her career seemed to consist mainly of false starts, enticing if fleeting indicators of an untapped potential. A classically trained soprano, she succeeded Madeleine Kahn and Judy Kaye as leading lady in the Broadway production of On the Twentieth Century, more than holding her own against Tony winners John Cullum and Kevin Kline. Two more high-profile Broadway assignments followed — as Ado Annie in the acclaimed revival of Oklahoma!, and Guinevere to Richard Burton's King Arthur in the actor's well-publicized return to the role he'd originated some 20 years earlier, in Camelot. She scored an Emmy nomination for her work on the soap opera One Live to Live, and had featured roles in Tootsie and Amadeus — performing her own singing in the latter as a tempestuous soprano who becomes the composer's mistress. After a disappointing season on Saturday Night Live, in which she was criminally underutilized, she made an ill-advised return to Broadway in the legendary flop Harrigan 'n Hart — better known to history as the Mark Hamill musical. She owned her few minutes as grind-house stripper Tessie Tura in Bette Midler's televised version of Gypsy, and found continued film work in projects as diverse as Kenneth Branagh's Dead Again, Clint Eastwood's True Crime and the Chris Farley/David Spade starrer Black Sheep.

The turning point in a long career of seemingly unfulfilled potential came with the 2001 revival of 42nd Street. Her pristine vocals and well-honed comic delivery helped her to rise above the mediocrity of a production, and earned her a Tony Award for her efforts. Other stage work soon followed, including acclaimed performances in Lincoln Center's production of Dinner at Eight, scoring another Tony nomination as a stand-in for Billie Burke, and off-B'way in Alan Bennett's Talking Heads. In Grey Gardens, she has found not one, but two roles of a lifetime, in a performance that has already netted her Drama Desk, Obie and Outer Critics Circle Awards, as well as a special citations from the New York Drama Critics Circle and The Drama League. Ben Brantley of The New York Times has hailed her performance as "one of the most gorgeous ever to grace a musical," which is not an overstatement.

The genius of Ebersole's work lies in her ability to navigate the extremes of both characters — she can be side-splittingly funny in one moment and heartbreaking in the next, without missing a beat. As Big Edie, a preening peacock who regards the world as her own personal stage, she is a delightful contraction in terms — the lofty, cultured imperiousness of a born grande dame coupled with the giddy enthusiasm of an attention-starved child basking in the glow of the spotlight. Blissfully unaware of her own ridiculousness, she treats everyone in her presence as an audience, with the breathtaking conviction of one who has never doubted that applause is her natural due; she literally comes equipped with her own accompanist. In the first act, Big Edie rehearses songs from her repertoire, which she intends to inflict upon the unsuspecting guests at her daughter's engagement party. Ebersole executes these pastiches with hammy relish -- including a hilarious minstrel number that would probably be considered in bad taste even by the standards of 1941. The brittle frivolity of this self-styled diva might brand her as a kind of outrageous, flaky cut-up in the Auntie Mame mold, if it weren't for the subtle flashes of panic and desperation that inform her neediness. The world that Big Edie has created for herself teeters on the brink of extinction — her husband, children and lover are all on the verge of leaving her — and the possibility of being left alone looms large on the horizon. A star cannot exist without satellites to orbit around it, and Big Edie fights desperately to keep her universe intact.

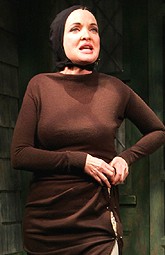

However, it is in the second act that the star of Ms. Ebersole shines the brightest. As the fretful child-woman only intermittently able to distinguish the line between fantasy and reality, her Little Edie is a mass of silly pretensions, wistful yearnings and seething resentments held on a slow boil over a period of decades. She inhabits the role with an eerie exactitude — in addition to capturing the unique look and posture of her real life counterpart, she recreates Little Edie's distinctive voice and cadence with uncanny precision (the accent is too strange to describe — imagine if John F. Kennedy and Katharine Hepburn had a daughter who grew up on Long Island). Rattling around the decaying house in grounds in a series of increasingly bizarre outfits with matching headdresses, she holds forth on a variety of topics in a style that might best be described as incontinent babbling — most of what she says is totally irrational ("They can get you in Easthampton for wearing red shoes on a Thursday, and all that sort of thing"), but the intensity and conviction of the speaker commands a peculiar kind of respect. She's at her happiest when left to revel in delusions of fame and romance waiting just around the corner — it's those piercing moments of clarity, when forced to confront the bleak realities of her present and future, that reveal how lost she truly is.

If there's a style of song that Christine Ebersole can't sing, the creators of this show haven't found it. The act opens with a rib-tickling, Sondheim-esque patter number in which Edie describes, in fastidious detail, her ideas about fashion, "The Revolutionary Costume for Today." It ends with a bittersweet ballad, "Another Winter in a Summer Town," that in the actress's hands becomes a haunting, harrowing anthem of despair and loneliness. Emotionally as well as vocally, she runs the gamut, and it's spectacular to behold. Special praise must also be reserved for the delightful Mary Louise Wilson, who scores a triumph in her own right as the elderly Big Edie. Needling her hapless daughter with vicious little digs (all delivered with an innocuous smile) and deflecting all rebukes with brisk denials, her sunny air of self-satisfaction makes a marvelous foil for Ebersole's prickliness.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Branagh, Documentary, Eastwood, K. Hepburn, Kevin Kline, Musicals, Sondheim, Television, Theater

Comments:

<< Home

Well done. My first exposure to Ebersole was her ill-fated appearance on SNL. Thanks for the heads up about the doc airing on TCM.

Post a Comment

<< Home