Wednesday, May 26, 2010

The Music of the Prequels: A Conversation

By Matt Zoller Seitz

and Ali Arikan

Matt Zoller Seitz: We gather here today to celebrate the talent, longevity and all-around wonderfulness of John Williams, whose work is being examined in a blog-a-thon. We're focusing on the Star Wars prequels because, after talking pretty extensively about Williams' long and prolific career, we mutually concluded that his work on the prequels represents his greatest conceptual achievement, and very possibly the summation of everything he knows about traditional film scoring.

And I suppose we should specify what we mean by traditional. I don't believe we're talking, Ali, about his more subtly colored, modernist work on such films as The Long Goodbye, or his historical spelunking in Steven Spielberg's historical epics (Schindler's List especially). We're talking about Williams in full-on Erich Korngold/Franz Waxman/Max Steiner mode, although personally I think Williams is more versatile and imaginative than any of them. More specifically, though, we're talking about what Williams does with that talent. We all know he's a master of a certain type of brash, rousing film score, the kind of score that's deployed in the service of what score composers often refer to, often disparagingly, as "Mickey Mousing." You know, Mickey Mouse sneaks across the screen and the score plays "sneaky" music. This composer (and conductor) is the absolute king, the Satchmo, the Hendrix, the Satchel Paige of Mickey Mousing. Nobody in film history can touch the guy. But what's different about the prequels is that he's doing what could be called, for a lack of a phrase, postmodern Mickey Mousing. He's doing what he did in the original Star Wars movies, even revisiting certain themes, but he's doing so with a really specific intent, you know?

Ali Arikan: One of my favorite moments in the history of the Oscars is the soundtrack medley of 2002 conducted by John Williams. In a fairly low key ceremony, the grandeur and awe of classic Hollywood cinema was briefly captured as Williams played a host of classic themes by Bernard Herrmann, Malcolm Arnold, Elmer Bernstein, etc. When it came to Alfred Newman’s 20th Century Fox fanfare, everyone knew exactly what piece of music it would be followed by: the main theme from Star Wars. To this day, every time I watch a Fox film and hear those magnificent horns, the nerd in me expects (hopes?) that it would be followed by Williams’ most famous Wagnerian fanfare. It is unrelenting, brash, and cheeky. Has any modern film composer been so bold with the brass section?

Interestingly, the theme begins almost in media res, which is fitting since so does the “first” film. Williams usually has a way of building up the melody, building up the eventual motif, but he forfeits this for the Star Wars Main Theme. In contrast, his Welcome to Jurassic Park, for example, has a lengthy and gentle piano, woodwind and string intro that eventually gives way to those majestic horns. Not so here. John Williams’s work in Star Wars is not just a part of the film, it is almost a metatextual narrator.

And this becomes even more apparent during the prequels. The way he manages to work in motifs from the original trilogy to new pieces of music is almost like the way Puccini played around with various themes in his operas. I think it’s safe to say that we can call the Star Wars scores — and I believe he scored around 15 hours of music for the entire saga — his magnum opus.

Matt: Yeah, absolutely. And maybe before we go deep-dish on Williams' contribution to the prequels, we should establish that in no way is this article meant to suggest that the prequels themselves are without flaw, or even especially consistent. On the micro level, they pretty much suck, in the way that the original Star Wars movies pretty much sucked.

Weak dialogue, wooden performances, too obvious symbolism. Harrison Ford's complaint to Lucas, "You can type this shit but you can't say it," was painfully true in a lot of cases. Where the original films excel is in creating an imaginative space, a mythology that plugs into nearly every culture and belief system — which is to say they excel at the macro level. That's no small achievement, and I don't think George Lucas gets enough credit for it. That's the pinnacle of popular art, creating something that enters the minds, the experiences, of hundreds of millions of people and becomes a reference point for, well, their lives. (Just the other day my son was asking me how long he would have to go to school and study science to learn how to build his own lightsaber. He's 25. I'm kidding, he's six.)

Weak dialogue, wooden performances, too obvious symbolism. Harrison Ford's complaint to Lucas, "You can type this shit but you can't say it," was painfully true in a lot of cases. Where the original films excel is in creating an imaginative space, a mythology that plugs into nearly every culture and belief system — which is to say they excel at the macro level. That's no small achievement, and I don't think George Lucas gets enough credit for it. That's the pinnacle of popular art, creating something that enters the minds, the experiences, of hundreds of millions of people and becomes a reference point for, well, their lives. (Just the other day my son was asking me how long he would have to go to school and study science to learn how to build his own lightsaber. He's 25. I'm kidding, he's six.)The prequels have even more problems at the micro level than the originals. In my New York Press review of Revenge of the Sith, I described Lucas as a filmmaker for whom the impossible seems to come easily, yet who can't seem to master, or else has no real interest in, the basics. I compared him to a prophesied sci-fi manchild who can levitate entire continents with his mind but can't master the use of a knife and fork. That said, there's some heavy-duty world creation, some heavy duty mythologizing, going on in the prequels, and if anything the films are much more conceptually sophisticated than the originals, and frankly more conceptually sophisticated than any other sci-fi or fantasy series, in terms of how they're constructed and what they're trying to accomplish. The trilogies mirror each other in all sorts of ways. And the mirroring is not only intentional, it's fiendishly exact.

To give you just one example, the scene in Revenge of the Sith where Mace Windu, the Emperor and Anakin have a three-way showdown in the emperor's throne room, the scene where Anakin turns to the dark side by turning against Mace.

The situation and the characters' predicaments evoke the throne room scene that ends Return of the Jedi: Vader's redemption. But if you watch the two scenes in succession, you'll see that Lucas hasn't just mirrored the throne room showdown from Return of the Jedi in Sith at a narrative level — the compositions and blocking often mirror Jedi's as well. Williams' score contributes mightily toward strengthening Lucas' mythic architecture. It sells the whole thing, makes it more energetic and heartfelt and persuasive. Williams does this by raiding his own cues for the original trilogy — doing with music what Lucas does pictorially. He doesn't just do it in the two big throne room scenes. He does it all through the prequels. He takes you down memory lane and says, "This scene is the cousin of another scene from the original series, or an ironic inversion of it, or contains elements of it, or is an answer to it." It's like he's superimposing the trilogies on top of one another by way of his own score.

The situation and the characters' predicaments evoke the throne room scene that ends Return of the Jedi: Vader's redemption. But if you watch the two scenes in succession, you'll see that Lucas hasn't just mirrored the throne room showdown from Return of the Jedi in Sith at a narrative level — the compositions and blocking often mirror Jedi's as well. Williams' score contributes mightily toward strengthening Lucas' mythic architecture. It sells the whole thing, makes it more energetic and heartfelt and persuasive. Williams does this by raiding his own cues for the original trilogy — doing with music what Lucas does pictorially. He doesn't just do it in the two big throne room scenes. He does it all through the prequels. He takes you down memory lane and says, "This scene is the cousin of another scene from the original series, or an ironic inversion of it, or contains elements of it, or is an answer to it." It's like he's superimposing the trilogies on top of one another by way of his own score.Ali: Definitely. Especially to the point that the main character, Anakin Skywalker, has two funerals. One, in Revenge of the Sith, when he is robbed of his former self by being turned into Darth Vader: we witness the fear in his eyes as the mask is lowered onto his face. The next is in Return of the Jedi, when, outwardly, he is Vader, but he has redeemed himself: the funeral pyre, lit by his son, signifying a sort of latter-day baptism with fire. Separately, both scenes work wonderfully well — together, they have a mythic quality.

The prequels were always going to be a hard sell. One of the most enigmatic lines from the original trilogy is Vader’s “Obi Wan never told you what happened to your father.” When I hear that, I think of grandeur and dragons and knights and all that good stuff. I don’t think of “YIPPEE!” Even though I do enjoy The Phantom Menace more than anyone I know, it was definitely not what I was expecting. Then again, and this might be a lot of fanwanking on my part, maybe that was the point.

Allow me to argue this from a musical point. John Williams obviously tried something different with the prequels. He wrote three overriding themes for each: Duel of the Fates for The Phantom Menace, Across The Stars for Attack of the Clones, and Battle of the Heroes for Revenge of the Sith. Nonetheless, I think if we were to name a secondary theme for the saga – the first one being the Force Theme — it would be Duel of the Fates. When the soundtrack for The Phantom Menace was first released, and I heard it, I remember thinking: “This sounds nothing like a Star Wars score, and yet it sounds exactly like a Star Wars score.” It was bizarre: first of all, you had that intimidating chorus in Sanskrit: “KORAH MAHTAH, KORAH, RAHTAMAH.” Apparently it means “Under the tongue root a fight most dread, and another raging behind, in the head,” but either Sanskrit is terribly economical, or that’s an apocryphal interpretation. Either way, even though Williams had used choral arrangements in Star Wars scores before (most notably during Luke’s final assault on Darth Vader in Return of the Jedi), never had they been in such prominence. Then you have this sense of inevitability, a sense of dread. Even though Duel of the Fates represents a constant struggle between good and evil, nonetheless, it seems rather certain that the bad guys will win: it’s no wonder that the only time it plays during the second prequel is when Anakin is searching for the Tusken Raiders who kidnapped his mother, and just before he massacres the lot of them. The way the strings and the horns crescendo is nothing short of breathtaking.

But I especially love the way it seems to end — and then doesn’t. Both the strings and the chorus continue subtly, as they give way to a final, much more violent crescendo, as if to reinforce Mace Windu’s rhetorical question to Yoda after the death of Darth Maul: “But which one was destroyed? The master or the apprentice?” Once again, Williams has worked into the music pieces from the narrative: you think this is over, but it’s only just begun.

Matt: Speaking of Duel of the Fates, one of my very favorite Williams moments is in the opening action sequence of Revenge of the Sith, maybe Lucas' peak as a choreographer of large-scale mayhem.

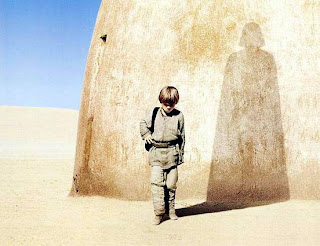

Anakin has rescued the Emperor, or at that point in the story the Chancellor, from General Grievous, and he has briefly saved Obi Wan as well. And now the chancellor's ship is crashing, burning up in the atmosphere, and Anakin has to pilot it safely down to a landing strip as it's crumbling. It's an amazing sequence in itself. But what pushes the whole thing up a notch — what makes it intelligent as opposed to just spectacular — is Williams' music. He's doing what I talked about earlier, superimposing one trilogy on top of the other. As you can see at the 10:38 mark in this clip, as the ship is making its final ascent, when we're seeing Anakin at the peak of his physical prowess and bravery, and he's saving the life of the man who will later rule the galaxy, and him, what do we hear? Duel of the Fates, which as you say is about the push-pull between the dark side and the light, and layered over that, The Force Theme, which I believe we heard for the first time in A New Hope in that iconic shot of Anakin's son Luke, the one who was really prophesied to restore balance to the force (sorry, Mace Windu!), staring out at the twin suns of Tattooine.

Anakin has rescued the Emperor, or at that point in the story the Chancellor, from General Grievous, and he has briefly saved Obi Wan as well. And now the chancellor's ship is crashing, burning up in the atmosphere, and Anakin has to pilot it safely down to a landing strip as it's crumbling. It's an amazing sequence in itself. But what pushes the whole thing up a notch — what makes it intelligent as opposed to just spectacular — is Williams' music. He's doing what I talked about earlier, superimposing one trilogy on top of the other. As you can see at the 10:38 mark in this clip, as the ship is making its final ascent, when we're seeing Anakin at the peak of his physical prowess and bravery, and he's saving the life of the man who will later rule the galaxy, and him, what do we hear? Duel of the Fates, which as you say is about the push-pull between the dark side and the light, and layered over that, The Force Theme, which I believe we heard for the first time in A New Hope in that iconic shot of Anakin's son Luke, the one who was really prophesied to restore balance to the force (sorry, Mace Windu!), staring out at the twin suns of Tattooine.  The Force Theme is such an optimistic, hopeful piece of music. It indicates great promise. And Williams is using it ironically and knowingly here, as if to say, "All the promise this kid displayed is about to cause untold harm to the galaxy — and this is it, folks. You're seeing the exact moment when everything turned to shit. It was the moment when he saved the chancellor."

The Force Theme is such an optimistic, hopeful piece of music. It indicates great promise. And Williams is using it ironically and knowingly here, as if to say, "All the promise this kid displayed is about to cause untold harm to the galaxy — and this is it, folks. You're seeing the exact moment when everything turned to shit. It was the moment when he saved the chancellor."Ali: I’m glad you bring up The Force Theme, because I’d love to hear your take on its significance over the entire saga. I would argue that this is the primary leitmotif of the films, and its appearance throughout the films triggers almost a sense memory. The first time we hear it is my favorite scene in the entire saga: Luke gazing into the binary sunset, as the melancholy motif subtly gives way to a perpetually progressive melody (it’s evocative of Jean Sibelius’ Symphony Number 4, the way it seems to tiptoe between joy and sorrow). It’s the epitome of the saga, isn’t it? The hero’s quest: not being content with the vagaries of life, the hero looks to the horizon, and the worlds unseen. What does Yoda say in The Empire Strikes Back: “A long time this one have I watched. All his life has he looked away to the future, to the horizon. Never his mind on where he was. What he was doing.” Luke wants more from life, he wants to be freed of the shackles of his surroundings: he seeks adventure. Despite being scolded by his uncle, despite his belief that he is never leaving Tattooine, despite the burden of mediocrity weighing down on his shoulders, a lingering feeling still remains in Luke as he gazes and imagines endless possibilities, and that feeling is hope. The hope that tomorrow will be better; that when adventure calls, he will prove his mettle. Ultimately, The Force Theme represents hope. Well, a new hope.

Matt: Yeah, and it's that hope that gets dashed in the prequels. That yin-yang you talk about in Duel of the Fates, the push-pull, is the thrust of the series, all six films. Nearly every major setpiece in the original trilogy is revisited in the prequels with a different conclusion, a different meaning. The original trilogy is the light side, the prequels are the dark side. And looming over all of it is Williams.

You know, in Japanese cinema there was a tradition, during the silent era, of this person called the benshi, or the explainer. He'd stand up at the front of the theater and interpret or almost mediate, if you will, between the story happening onscreen and the receptive audience out there in the dark. Williams is the benshi of the Star Wars movies, the explainer. He's not just italicizing and underlining things to make sure we get them — although this is a very old fashioned type of film storytelling, so there's an aspect of that in his mission. He's also teasing out deeper resonances, and perhaps — though a part of me hates to say this because I've already stated that I don't think Lucas gets enough credit as a mythmaker — maybe Williams is adding a lot as well.

There are times when I feel like he's the second editor on the series, perhaps over and above the editing team that put the footage together. He's an editor in the publishing sense — an eye in the sky who isn't trying to make a writer into a clone of himself, but who appreciates the writer for what he is, and wants to help him be the best him that he can possibly be. Williams' music helps Lucas be Lucas. I feel almost as if Williams figured out what Lucas was trying to say in particular moments and sequences and found a way, musically, to say it for him.

Ali: Funny you should mention the benshi, because the piece of music that plays as the Federation cruiser crashes into Coruscant is the same one that does during the final salvo of the space battle in The Phantom Menace. Whereas Anakin infiltrated the belly of the beast to destroy it in the first prequel, in Revenge of the Sith, he is saving the very beast that orchestrated the whole thing. Once again, the theme, the modern-day benshi, is doing the narration.

Another favorite is the aforementioned Across The Stars theme from Attack of the Clones. As Anakin and Padme are being wheeled into the Geonosian arena to be executed, Padme admits her love with the clumsiest dialogue in the entire saga (which is a feat, in itself): “I truly, deeply, madly, other-pointless-adverbly love you,” she says, and kisses Anakin. Despite the shortcomings of the dialogue, it is, nonetheless, a magnificent shot: the camera stays behind the two prisoners, who are initially obscured in the shadows, as they emerge into the sun-drenched arena. The camera then follows Anakin’s pov as he surveys the insectoid crowd voracious for their bloody demise. Across The Stars, in D minor (saddest of all keys), plays throughout the scene, and lends it a sense of tragedy: not because of any instantly impending doom (since we know they get out of this alive), but because of how their love will end: one will turn into an evil cyborg, the other will perish. Unlike the love theme from The Empire Strikes Back, Across The Stars has no hint of frivolity: it is a tragic theme for a pair of star-crossed lovers. So sad. It’s a classic.

On the whole, the prequels represent something truly bizarre: a seemingly child-like tale that ultimately gives way to despair. The most colourful locales, juvenile characters, and — on the surface, at least — whimsical stories end with total destruction. Lucas is a master storyteller, and, obviously, the Star Wars saga is his life's work. But he would not have been able to create such a universal fable out of it were it not for his most consistent lieutenant: John Williams.

Tweet

Labels: Blog-a-thons, Harrison Ford, John Williams, Lucas, Music, Spielberg, Star Wars

Comments:

<< Home

Nice work, guys! I still haven't caught up with Episodes II and III, but this discussion—of the music, of all things—actually makes me want to finally fill in those blind spots.

I may have more to say about this in my own contribution to this blog-a-thon, but John Williams was probably the first film composer I was aware of when I was really young; only through knowing Williams was I able to get to know the work of Bernard Herrmann, Jerry Goldsmith, Elmer Bernstein and the rest of 'em. So in that sense, the man's important to me.

I look forward to reading what else this blog-a-thon has to offer!

I may have more to say about this in my own contribution to this blog-a-thon, but John Williams was probably the first film composer I was aware of when I was really young; only through knowing Williams was I able to get to know the work of Bernard Herrmann, Jerry Goldsmith, Elmer Bernstein and the rest of 'em. So in that sense, the man's important to me.

I look forward to reading what else this blog-a-thon has to offer!

Very nice blog, just wanted to point out to Matt though that Anakin is in fact the chosen one, it's by destroying Palpatine (which Luke wasn't capable of doing) that Anakin brings balance back to the Force, Lucas has said so himself.

It should be noted that the music that plays while Anakin lands the ship is actually recycled from Episode 1, as is a lot of the stuff from 2 and 3.

Post a Comment

<< Home