Friday, December 15, 2006

Vertically Challenged

By Josh R

This past week, much of the media's attention has been focused on the report of The Iraq Study Group, under the supervision of former Secretary of State James Baker and former Rep. Lee Hamilton. The group had the unenviable, if not impossible task of trying to make some modicum of sense of the unruly mess that Team Bush's Excellent Adventure in the Middle East has undoubtedly become. The conclusion seemed to be that no easy conclusion is possible given how rapidly the situation has degenerated, and solutions become increasingly less available the longer we proceed without a decisive strategy to implement — which is to say, we need a clear direction, whatever that is.

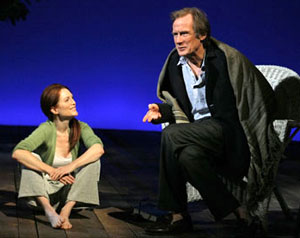

The Study Group might draw the same conclusion if forced to ponder, weigh and generally try to make sense of The Vertical Hour, the new play by David Hare that has just opened at Broadway's Music Box Theatre featuring the estimable talents of Bill Nighy and Julianne Moore. Fittingly, the subject of the play is The War in Iraq — at least, that's the overall impression I got from watching it. Honestly, I may be wrong, given how many conflicting, seemingly contradictory ideas seem to have been shoehorned into the space of two and half hours of discussion. Like the current state of Iraq, on which its debate is centered, The Vertical Hour is thorny and muddled, with various ideas bouncing off of each other so haphazardly as if to make a plate of scrambled eggs look like a model of order. Convoluted to the extreme, it doesn't really seem to find any clear answers to the questions it poses...and believe me, that's a whole lot of questions.

The basic plot structure is simple enough, in and of itself. A British expatriate brings his American fiance (Ms. Moore) home to meet his father (Mr. Nighy), a doctor living on an isolated country estate on the Welsh border. What follows the obligatory introductions and pleasantries is a complex ideological struggle — and all this before anyone has had the chance to sit down to dinner. The fiance, a former war correspondent who now teaches political science at Yale University, has achieved some measure of success (and notoriety) as a televised talking head with controversial positions on American involvement in Iraq. Without being patently right-wing or anything close to it, she feels that American intervention is justified by the need to put an end to the kind of atrocities she witnessed during her reporting stints in Baghdad and Bosnia. She's less concerned with WMDs than with moral imperative — the notion that we have a duty to alleviate suffering where it exists. Her prospective father-in-law is inclined to view Bush policy as an unqualified disaster, and can't allow for any moral justification for our military presence in Iraq. The fur doesn't exactly fly — these are civilized people, after all — but there's an awful lot of philosophical debate.

Sounds simple? It might have been, had Hare remained focused on his primary objective, that of illustrating the cultural differences between America and Britain, specifically in terms of our attitudes towards the War in Iraq. Moore and Nighy are supposed to represent the two sides of that cultural divide — the American way of thinking as opposed to the British — but the playwright tosses so many other ingredients into the pot that the basic premise gets jumbled.

Since their basic positions might seem too straight-forward in and of themselves, Hare leads us to understand (well, he tries to) how both characters have been conditioned and shaped by their own complex pathologies. Years of bearing witness to the theater of Third World brutality and ethnic cleansing from a front-row seat have made Moore's character a prisoner of her own rage, regarding the complacency of superpowers and their citizenry with bitterness. This anger has made itself manifest in her approach to personal relationships, and she's not drawn to her would-be groom for the reasons that she necessarily thinks she is. The doctor's mixture of resignation and laissez-faire idealism is partly the product of his attitudes towards romance and sexual gratification (much is made of his preference for "open" marriage) and the residue of guilt he lives with from his involvement in the death of his mistress. There is ample discussion of the theories of Sigmund Freud, who gets enough shoutouts to qualify him for his own program credit. The characters ponder the death of heroism as the inevitable consequence of the end of The Cold War, the role of patriotism in society and the mutable properties of identity. The title of the play is a medical term which refers to the window of opportunity during which a physician can still be of use to a critical patient and effect the outcome. I'm not sure what this has to do with anything, but it's in there; I suppose you could say the doctor manages to "fix" the woman by bringing her around to an altered point of view, but I'm not sure that's what happens exactly. Oh, yes ... and Nighy's character may or may not be trying to seduce Moore, something she may or may not be receptive to, depending on how you look at it.

I suppose what Hare is really trying to say — and again, I'm guessing here — is that we all have our own messy personal baggage which informs our political views, and that none of us is really capable of approaching thorny issues from an objective position. No one is exactly wrong, but no one is entirely right, either.

Unless some of us are right.

I think.

The actors navigate this tangle with an admirable degree of skill, although they are understandably hampered by the limitations of the material and the challenge of trying to bring a sense of cohesion to the proceedings. Nighy makes a remarkably assured Broadway debut, bringing a weathered, laconic charm to his portrayal of man whose resigned outlook masks a spirit of restlessness and unresolved feelings — "Physician, heal thyself" has never seemed so apt. Moore has the much more difficult task of bringing human dimension to a character who exists on a much more conceptual level — that she manages to pierce through the confusion and bring a sense of emotional truth to Hare's garbled rhetoric is a testament not only to her talent, but her intelligence as a performer. The deck is certainly stacked against her — to say that Hare skews in favor of the British point of view in this cultural showdown is an understatement. I suppose I would find his view of the American mentality offensive — that is, if I were fully able to grasp exactly what he was trying to say about it. At this point, I'd rather ship a copy of the script off to Baker and Hamilton to let them have a crack at it.

Tweet

Labels: Julianne Moore, Theater

Comments:

<< Home

Of the Hare stuff I've seen on Broadway, I loved Skylight and Via Dolorosa the most. Amy's View would have been nothing without Judi Dench. The Blue Room and The Judas Kiss were both bores. Plus, I'll never forget that he was responsible for the snoozer of a screenplay for that snoozer of a movie The Hours.

Post a Comment

<< Home